Which bar are we talking about?

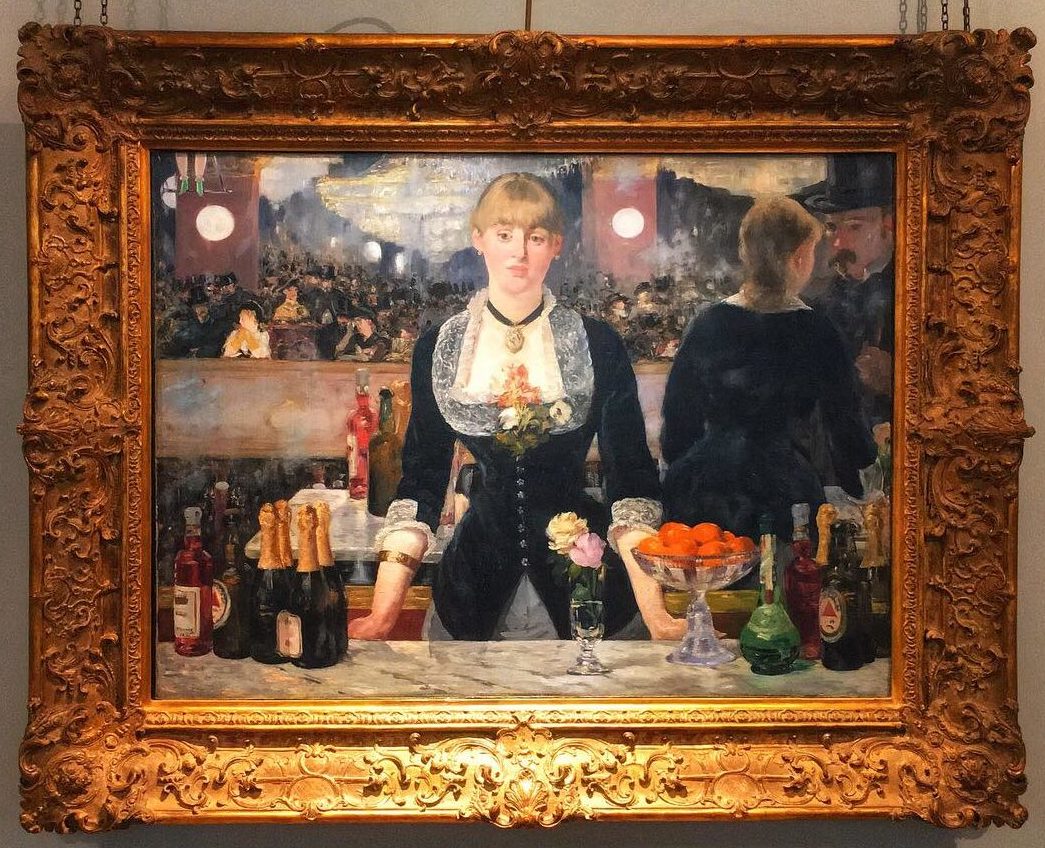

The Folies-Bergère, of course! The notorious 19th century Parisian music hall where water turns into champagne, and leisure into pleasure. And where nothing is what it seems. Edouard Manet’s depiction of the venue, entitled “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère†(1882) shows exactly what it claims: the exuberant Folies-Bergère vanity fair coming together under a crystal chandelier, whilst a young barmaid stands at a marble counter between champagne bottles and a bowl of oranges.

As Impressionists pledged allegiance to pinning down the fleeting wonders of modern life, Manet’s topic is in no way unusual. The artwork itself is however a culmination of both Manet and Impressionism: the best of vivid illusions in quick, lavish brushstrokes.

Why is this relevant now?

Ironically, Paris’ famous bar is a Londoner. And it has moved house: part of the Courtauld Gallery’s permanent collection, “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère†and its Impressionist royal family are temporary residents (the Courtauld is undergoing renovations) of the National Gallery. You can pay the Folies-Bergère’s barmaid a visit in her Trafalgar Square home at the “Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne†exhibition until 20 January 2019.

Who’s that girl?

That’s Suzon. She was a genuine barmaid at the Folies-Bergère, offering oranges… and maybe more – French novelist Guy de Maupassant described the barmaids as “vendors of drinks and loveâ€.

The rest of Suzon’s story is a helpless enigma, much like her expression. English author Philip Pullman claims “she is far more mysterious than that smirking Florentine we know as the Mona Lisaâ€. Yet we can’t help but try solving it. Is she dreamy, melancholic, alienated? Or perhaps just tired? Corseted in a moment in time, Suzon’s gaze escapes the canvas to a secret place, almost caressing the viewer’s ear on its way there. There’s a certain duplicity about her character; the presence of a mirror also reflects this.

Wait, there’s a mirror?!

Yes, there is! The glittering crowd is a reflection of itself in the bar mirror behind Suzon: the show on display is actually the music hall audience. Detached from it all, the barmaid is the still counterpoint to an ever-turning world, its dizzy simultaneity invoked by hurried brushstrokes.

But the mirror is not the only thing hidden in plain sight. Have you noticed the emerald slippers belonging to a trapeze acrobat on the top left corner? Look again. The mirror also reveals a dark stranger, moustache and top hat included, leaning towards Suzon. There is something menacing about his presence – or rather absence from Manet’s visual field. Is the gentleman Manet himself? Is it us, the viewers? Unlikely, answers art historian Malcolm Park who created a photographic reconstruction of the composition, concluding the viewer must be standing somewhere on the right. Nevertheless, the puzzle of Manet’s intentions remains unfinished: there are claims that his choice makes no sense; there’s a book called “12 Views of Manet’s Barâ€. There is no final piece.

Was Manet under the influence?

Manet certainly did take more than a few field trips to the Folies-Bergère, but the painting was entirely created in his studio. However, it is speculated that he was under some other kind of influence: Velasquez’s. The Spanish painter’s “Las Meninas†(1656) is a statement about mirrors being the cleverest and most unsettling tricks to tell a story. It is not difficult to imagine Manet, a fan of Velasquez, accepting this indirect challenge: turn his canvas into a mirror reflecting modern life as an open-ended mystery novel.

Photo credits: Irina Anghel