Staff writer Katharina Kayser discusses the issue of female genital mutilation and the best ways to end it as a practice.

Editor’s note: This piece contains content which some readers may find distressing.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is an inhumane practice that has been around for several hundred years and is internationally recognised as a violation of human rights, health and the integrity of girls and women. 6 February is the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). The process has no health benefits and is conducted mostly for cultural or religious reasons. Therefore, it must be addressed.

Currently, more than 200 million women have suffered from FGM. In 2025, 4.4 million girls risk undergoing FGM, which is roughly 12.000 cases per day. This means we must act as soon as possible. As the UN has the goal of eliminating FGM by 2030, we as a society must raise awareness of the issue of Female Genital Mutilation. We have to look at what we, as a collective and individuals, can do to make the future a more equal and safe space for girls and women.

What is Female Genital Mutilation?

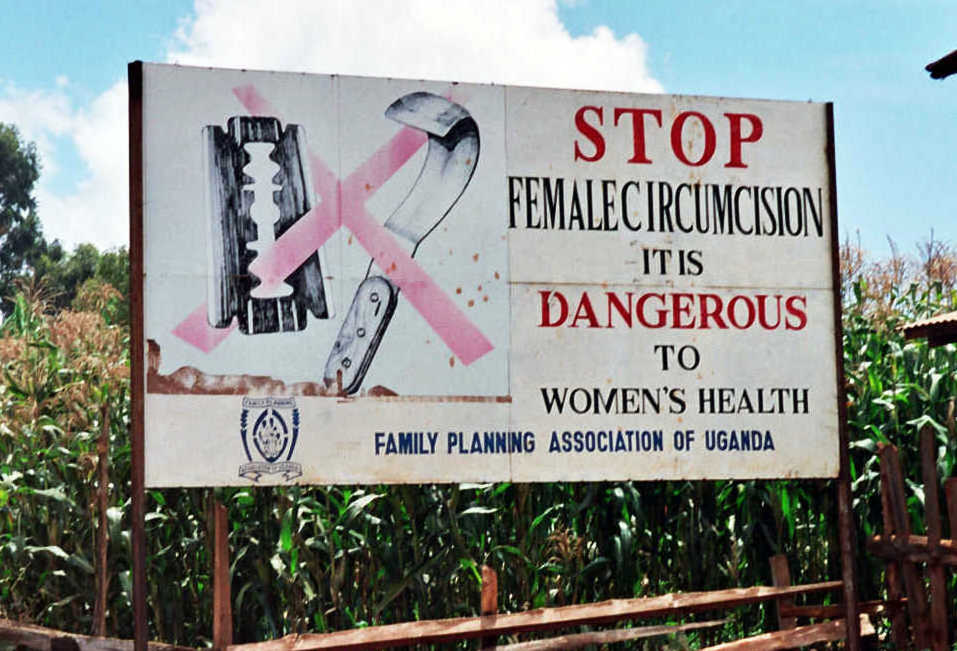

Female Genital Mutilation is a procedure where the female genitals of young girls or women are deliberately cut, injured or changed. It is also known as female circumcision, cutting, Sunna, gudniin or halalays among other names. Normally, it is carried out between infancy or before puberty starts, up to around the age of 15. There are four main types of internationally recognised FGM.

Type one: “clitoridectomy” refers to the removal of part or all of the clitoris. This form is regularly conducted when society deems girls as unclean. The clitoris enables you to experience sexual pleasure.

Type two: “excision” refers to removing part or all of the clitoris as well as the inner labia, with or without the removal of the labia majora. The inner labia describe the lips that surround the vagina and labia majora stands for the larger outer lips. This type is often carried out as a means of transition from girlhood to womanhood. Part of this initiation ritual is that girls are not allowed to scream or cry during the FGM procedure. Seemingly to prove that she is now an adult and can take on new societal responsibilities.

Type three: “infibulation” refers to the narrowing of the vaginal opening by creating a seal. This seal is formed by cutting or repositioning the labia. The seal in the form of a small hole is supposed to be the opening through which women can urinate and menstruate. As the opening is so tiny, no penetration will be possible. Communities where the sole worth of women depends on their virginity often perform this type. Sex during their wedding night or childbirth is extremely painful and likely to bring back the initial trauma of FGM. This is deemed FGM’s most destructive form.

Type four refers to any other forms of pricking, piercing, cutting, scraping or burning of female genitals that can’t be justified for medical reasons. Some practices such as touching female genitals with magical crystals, even though not leaving any physical marks, still fall under Type four as they are performed to control female sexuality.

Normally, FGM is performed by traditional circumcisers or cutters who do not have any medical training. Efforts that were centred on minimising the health risks of the practice resulted in a medicalisation of FGM, where the procedure is performed by a medical practitioner. Not only does this medicalisation of FGM give false legitimacy to the practice. But it is also rejected by many practitioners as it is seen as “a potential challenge to the central and authoritative role of traditional circumcisers”.

It stands, however, that these efforts do not eliminate physical or psychological pain and do not make the procedure less violent and inhumane. Girls and women still suffer from immense pain and long-term health problems such as complications during childbirth or urination.

FGM is traditionally performed in many parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. In countries such as Senegal, where FGM has been illegalised, the practice has continued to be performed in the underground. As the practice persists with immigration populations in Western Europe, North America, Australia or New Zealand, with increased in immigration flows it becomes an international concern.

Female Genital Mutilation has therefore also arrived in the UK. Girls whose families originate from an FGM-practising community but are residents in the UK have an alleviated risk of FGM happening to them. According to University College London & Equality Now, in 2011, around 137,000 girls living in Wales and England were affected by FGM. The highest number of cases is in London. In some instances, girls are being taken on a vacation to receive FGM without their knowledge.

The FGM ACT 2003, as well as other legislation such as the Serious Crime Act 2015, declared the practice illegal in the United Kingdom. Some women “believe that the law in the UK is an effective deterrent to FGM when they visit their country of origin due to the pressure for the girl to be circumcised”. The Tackling Female Genital Mutilation Initiative has worked towards preventing FGM from happening in the UK during the past 15 years. They have played an essential role in advancing legal protection of girls from the procedure and provide support for victims of it.

“Ending female genital mutilation is essential for achieving gender equality, ending all forms of gender-based violence, and empowering women and girls world wide”

The inhumane nature of FGM

25% of affected girls and women die, either during the procedure or from health repercussions after. The procedure itself is extremely painful. It is normally carried out without anaesthetics. FGM is, furthermore, usually performed with knives, scissors, pieces of glass or razor blades. According to The Independent, in the countries where it is performed, FGM “causes over an estimated 44,000 excess deaths of women and girls”. These deaths result from a loss of blood or infections that were transmitted during the procedure.

FGM is very painful and can lead to serious harm to the long-term health of girls and women. Severe pain, shock, organ damage, menstrual problems, vaginal and pelvic infections and incontinence to just name a few. Girls affected have issues during sex. Not only is sex very painful, but women report that they have less sexual desire and notice a lack of pleasurable sensation. Furthermore, childbirth (if still fertile) risks being extremely painful. Most women suffer from problems when urinating or menstruating. Furthermore, women risk bleeding or getting infected with HIV, tetanus or hepatitis during the procedure.

Besides physical health issues, women suffer long-term mental trauma from FGM. Depression, insomnia, anxiety or PTSD are not uncommon. FGM takes away a girl’s future by stripping her of a basic aspect of her humanity. Girls and women are denied the right to choose what happens with their body; they are being violated against their will and made to feel bad if they oppose the practice. In some cases, it is performed on newborns!

Another aspect that makes FGM so cruel is that it is a non-reversable practice. Surgery can be performed to open up the vagina of a woman who has been infibulated again. This surgery is called deinfibulation. The name, however, is misleading as it will not restore removed tissue. It can, nonetheless, help with health problems caused by it, such as facilitating childbirth or simply urinating and menstruating.

Even though there is awareness regarding the suffering that comes from FGM, it is still practiced in many communities. This is unacceptable and emphasises that equality is far from being a reality anywhere in the world. As MEP Maria Noichl said, “unfortunately, the female body is a battlefield. (…) It is always about the control of men over women’s bodies”.

Why is FGM being performed?

FGM is deemed illegal and child abuse in the UK. This is taken very seriously, as anyone who performs FGM in the UK can face up to 14 years in prison. Anyone failing to protect a girl from FGM can face up to 7 years in prison.

Nonetheless, people performing FGM claim to do so for several cultural, religious and social reasons in the mistaken belief that it will benefit the girl in some way. For example, FGM is often justified as a preparation for marriage or a means to preserve a girl’s virginity and access to inheritance. Other communities see the mutilation of female genitals as a rite of passage into womanhood. In general, girls whose mothers have also undergone FGM are at a higher risk of suffering from it. Across groups performing the mutilation, the practice is used to control a girl’s sexuality and ensure her purity and fidelity for marriage. Moreover, social and group pressure influence the keeping alive of the practice as well.

It must be added that FGM is often performed to fulfil societal pressure. A woman from rural Gambia stated that “even the children insult their mates who are not circumcised as ‘soleme’. It is common to hear children calling their fellow children: ‘You solemas, you will not follow us'”. This demonstrates that as FGM is culturally ingrained in many communities, performing it is seen as a societal duty as otherwise, the girl as well as the family, face severe judgements and exclusion from their community. This shows how perfidious the procedure is.

In other contexts, FGM is often justified by religion. This is a misinterpretation, however. Major religions like Islam or Christianity do not endorse but condemn this practice. Furthermore, some claim to perform FGM to enhance female hygiene. In many cases, the female genitals are mutilated to enhance male pleasure as well.

How to fight FGM internationally

There are two stages. First, survivors of FGM must receive immediate and comprehensive care. There must be a general effort to create safe spaces for girls and women. We must create environments where girls and women have the right and power to make choices. We must ensure that every female person can enjoy their rights to health, education and safety.

In England and Wales, for example, people can apply for an FGM protection order (FGMPO). These protection orders are a way to protect girls who are or are at risk to be a victim of FGM. It does so by providing legally binding prohibitions and restrictions, such as taking away a girl’s passport to prevent their family from taking them abroad.

Additionally, we must safeguard every woman’s access to medical care after having undergone FGM. A Joint Programme between the UNFPA and UNICEF since 2008 leads the biggest global initiative to eliminate FGM. It currently focuses on 17 countries and has seen many achievements. Through this programme, more than 7 million survivors of FGM received care services, prevention and protection from FGM.

Second, the root of the practice has to be neutralised. The UN, as well as several other countries, have undertaken the first important step of banning FGM and declaring it an illegal practice. A female respondent of the Manor Gardens Welfare Trust stated that the law prohibiting FGM provided women with the power to say no. She expanded that “if the woman is educated, she can use the law to threaten the father or the mother-in-law that she will go to the police if they try to have her daughter cut”. The value of creating safe spaces where both men and women can freely talk about their experiences with FGM has been felt by many people.

Moreover, conversations with traditional community leaders have to take place. Initiatives such as the Tostan’s Community Empowerment Program have demonstrated that reaching leaders of FGM-practicing communities is key to abandoning the practice.

In addition, influential members of their communities should not be forgotten in this context. Men and boys as husbands, fathers and brothers, are just as likely to oppose FGM as women. Their influence in communities should be used to raise the issue and help FGM be stopped.

A PEER research study has demonstrated that in the last decade, FGM has become less of a taboo. More mothers have started to speak up and protect their children from the practice. Interestingly, however, it is especially young women who cling to FGM due to them marrying early. Through the support of the practice, they gain social support and acceptance from their extended families.

Research has shown that “older women are uniquely positioned to realise the dual goal of honouring tradition while negotiating change”. Scholars found that these women have an appetite for reform that maintains the physical well-being of the younger generation. Given their traditionally higher status of respect and authority, “they also have the power to negotiate change”. Therefore, older women as well as men can be a key to changing the system.

What can YOU do?

If you know anyone who is at risk of FGM in the UK contact the NSPCC helpline on 0800 0283550 or email [email protected]. If you have suffered from FGM there are several medical practices and information centres that can assist you. Visit this website for more information and access to help: National FGM Support Clinics – NHS – NHS.

Moreover, you can contribute financially to support the fight on FGM. Funding to end FGM recently has gone down, especially for women’s organisations and survivor-led movements. In general, it is always important to spread awareness and use ones voice to raise the issue. Be it at the next flat party, Friday night dinner with the parents or the next seminar discussion about female rights and equality.

If we do not change anything, if we don’t raise our voices to make the problem a priority in people’s minds, then an estimated 27 million girls risk undergoing Female Genital Mutilation by 2030.

Katharina Kayser is a second year "European Studies with the French Pathway" student at King's College London.