Science Editor Jana Bazeed chats all things maths, Pokémon and outreach with mathematician Dr. Tom Crawford (Tom Rocks Maths) following his talk at New Scientist Live 2024.

“Take a Magcargo to be a Sphere”

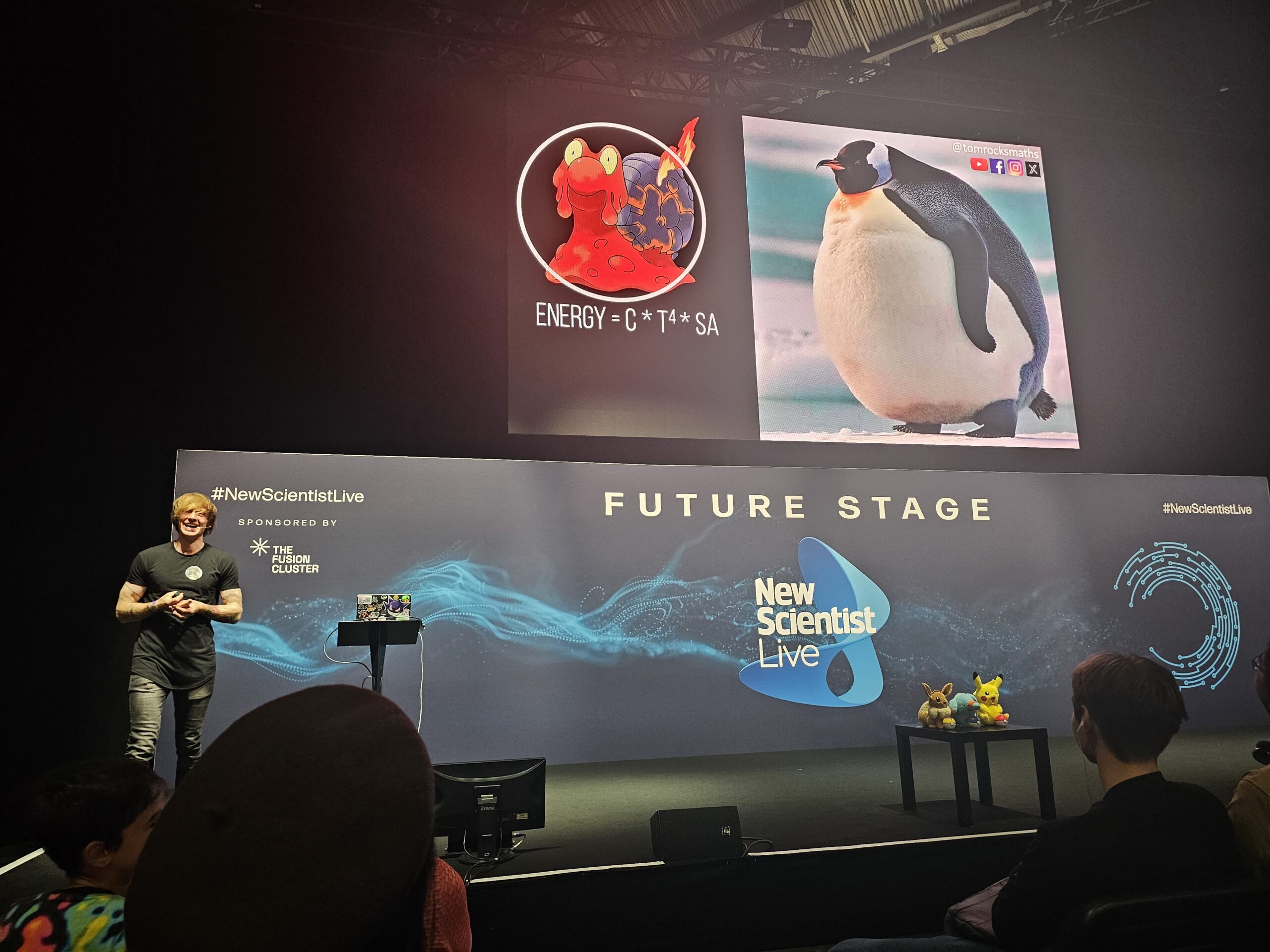

On 13 October 2024, Dr Tom Crawford took to the Future Stage at New Scientist Live 2024 to answer some of the modern age’s most pressing questions for today’s mathematicians: what’s up with the physics of Pokémon, and how much would food would one need to sustain a pet Charizard?

These questions–and many more–were answered during his talk, ‘Pokémaths – the maths behind the video game‘. The talk proved to be an playful display of the powers of mathematical modelling, keeping a diverse audience of all ages engaged.

Tom Rocks Maths

Crawford is a mathematician at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. When he’s not teaching, Crawford dedicates his time to making mathematics fun and accessible:

“When I’m not teaching, which is a lot of my time, I am getting far too excited talking about maths in front of a camera for YouTube or in front of an audience like today.”

Crawford’s YouTube channel, Tom Rocks Maths has recently surpassed 200,000 subscribers and 25 million views. He credits his start on the platform to a suggestion from his students:

“When I was PhD student in Cambridge, I was doing lots of teaching, because I enjoy it, and it pays pretty well—especially as a PhD student. I remember there was one particular thing in vector calculus I was teaching the first years, and they just didn’t get it from the lecture. Then I explained it, and they were like, ‘Oh, it makes so much more sense now’.

And then, the next week, they were like, ‘Can you re-explain that? Because we tried to do it for our friends, but we feel like we messed up your explanation.’ In the end, they end up recording a really short, terrible video on my phone. Just me explaining this, and then they send it to their friends. Then they sent it to some other friends at some other university. So then, you know, they were like, “You should really put this on YouTube.” I didn’t put that on YouTube, but I think it planted a seed in my mind that if students are sharing it themselves, then maybe the way I am explaining things is actually helpful and different.”

According to Crawford, this encouragement, combined with an internship producing a science radio show for the BBC, was what gave him the final push to start making YouTube Videos:

“During my PhD, we had a BBC internship advertised […] It was very specific: something like ‘We are looking for a maths PhD student at the University of Cambridge to come and work with us for eight weeks to make a science radio show.’ Well, that’s not that big of a pool of people, so I thought, ‘You know what, that sounds fun, let’s give it a go!’ […] I ended up getting the placement, did it for eight weeks, and just really, really enjoyed it. So, I think that kind of media communication stuff, combined with already being into teaching and my students telling me that they should record the stuff that I’m teaching. I think the two just came together, and then I started making YouTube videos.”

Besides YouTube, the mathematician has ventured into various forms of mathematics outreach, be it through his work as the Public Engagement Lead at the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education, his award-winning website, or guest lectures at the Royal Institution.

“This, to me, feels like playtime.”

For Crawford, Mathematics is a life-long passion:

“I don’t remember a specific point where I was, like, ‘maths is my thing’. I think that’s because it’s just always been my thing. I think the oldest memory I have is doing long multiplication in year four at primary school, and just thinking it was cool. And I just wanted to keep doing more and more questions! […] I was just like, this is fun, and I enjoy it. And this, to me, feels like play time.”

Although Crawford cites the certainty of maths as one of the key things that drew him to the discipline, he feels that the room for creativity in problem-solving is often underestimated:

“I think something I didn’t realise when I was a student is how creative solving a maths problem can be. Because I think often, you’re just trying to get through whatever problem set you’ve got to do and looking for similar examples in the textbooks or the lectures, and you’re just kind of like, “I’ll do it this way, because that’s what it looks like.” And, you know, and that is, I think, the way you’re kind of meant to do it as an undergrad. But then the more I’ve kind of gone on with maths, I began to realize, and I even see it now actually, in the way that I teach, is [that] there are so many different ways to solve a problem.”

He encourages students to think outside of the box, and challenge their mathematical intuition:

“Yes, there’s one answer, and I think that’s part of why I enjoy maths, to have that binary, of ‘this is correct’ or not. I quite like the certainty of it. I think I maybe focused on that too much [as an undergraduate], whereas now I began to realize it’s actually very creative and playful. I could go about saying “Okay, so I’ve solved this problem using this particular proof and this method. What if I can’t do it this way? What if I’m not allowed to use this method? How would I do it now? Can I do it now?” Just kind of thinking about things in that way, to me, actually makes you a better mathematician. Especially when you’re trying to go on to research level.”

Fool-proof Proofs?

When asked about his top tips for students, he laughed:

“When you’re doing a proof (I can’t believe how well this works) and you can’t begin, or you look at it and you’re stuck, often just taking basically every word or condition that’s mentioned in the proof and just writing out its definition or what it means gives you 95% of the proof. It’s insane! […] That’s not to say it will always work, but when you’re stuck on a problem, just write out all of your definitions and it often your brain spots something that helps you actually solve it.”

For more of Roar’s coverage of New Scientist Live 2024, click here.