Staff Writer Eleanor Long counters criticisms against BookTok, arguing for its potential to inspire a love for reading in the younger generation.

This article was originally published in print on 28 November 2024.

Bland, shallow and performative – those labels summarise the reputation BookTok has accrued recently. However, those criticisms eclipse the joyous resurgence of young readers: in the shadows, forgotten by many adult critics, are teenagers passionate about literature and seeking a community.

So, I decided to speak to a 14-year-old student. “BookTok has made being a reader cool again. Stereotypically, teenagers find books very boring, but this is changing that”, they said.

But what is BookTok? With over 200 billion views under #BookTok, it’s hard to put this vibrant TikTok sub-community into a single definition. Still, a love for reading unites it all. Creators from across the world share short videos, recommend their favourite books and leave reviews.

Although their influence has blossomed in recent years, online reading communities are not a new phenomenon. In 1634, Anne Hutchinson founded one of the earliest known book clubs on a ship from England to Massachusetts where women met to discuss the Bible and weekly sermons. It’s therefore no surprise that book clubs have persisted in the technological age. Today, together with its predecessors BookTube and Bookstagram, BookTok is connecting an even greater number of people worldwide.

Sure, some strong criticisms of BookTok, particularly the lack of diversity and its influence on the publishing industry, hold force and should not be ignored. However, I want to shine a light on its positive impact on young people and their reading habits.

As …. told me, the shift towards the identity of ‘a reader’ is an extremely welcome development, given the “increasingly visible downwards trend in reading enjoyment” a National Literacy Trust report revealed. Their survey found that only two in five people aged 8 to 18 enjoyed reading for pleasure in their free time, the lowest since 2005.

BookTok’s algorithm is one of the greatest weapons the platform has against such alarming results. TikTok’s For You Page is a personalised feed tailored to the user’s interests and interaction with content. This personalisation is paramount to engaging young readers. It makes them more likely to find a book they like or a protagonist they can relate to. Similarly, as an English tutor, when I recommend fiction, I adjust it to my students’ interests. If you love football, read a football book! There should be no shame in reading for subjective pleasure.

Have you ever read a book that made you fall into a reading slump? That may be a small hurdle for passionate adult readers, but a massive obstacle for readers who are just starting out. That’s why the curation of book recommendations may be the spark emerging readers need. It achieves what we, tutors, wish we could. So, until teachers and librarians develop mind-reading skills, I pass the baton to BookTok to help us out.

Indeed, it seems to work. “I’m encouraged to read a book after seeing it recommended on TikTok,” said a year 9 student. “I’m more likely to pick it up because I know that if [creators] are suggesting it, they enjoyed it so much they want other people to read it and have the enjoyment too”, they said. The same contagious enthusiasm for literature is echoed in a poll from the Publishers Association in 2022 in which nearly 60% of the surveyed, aged 16-25, said that BookTok or book influencers helped them discover a passion for reading.

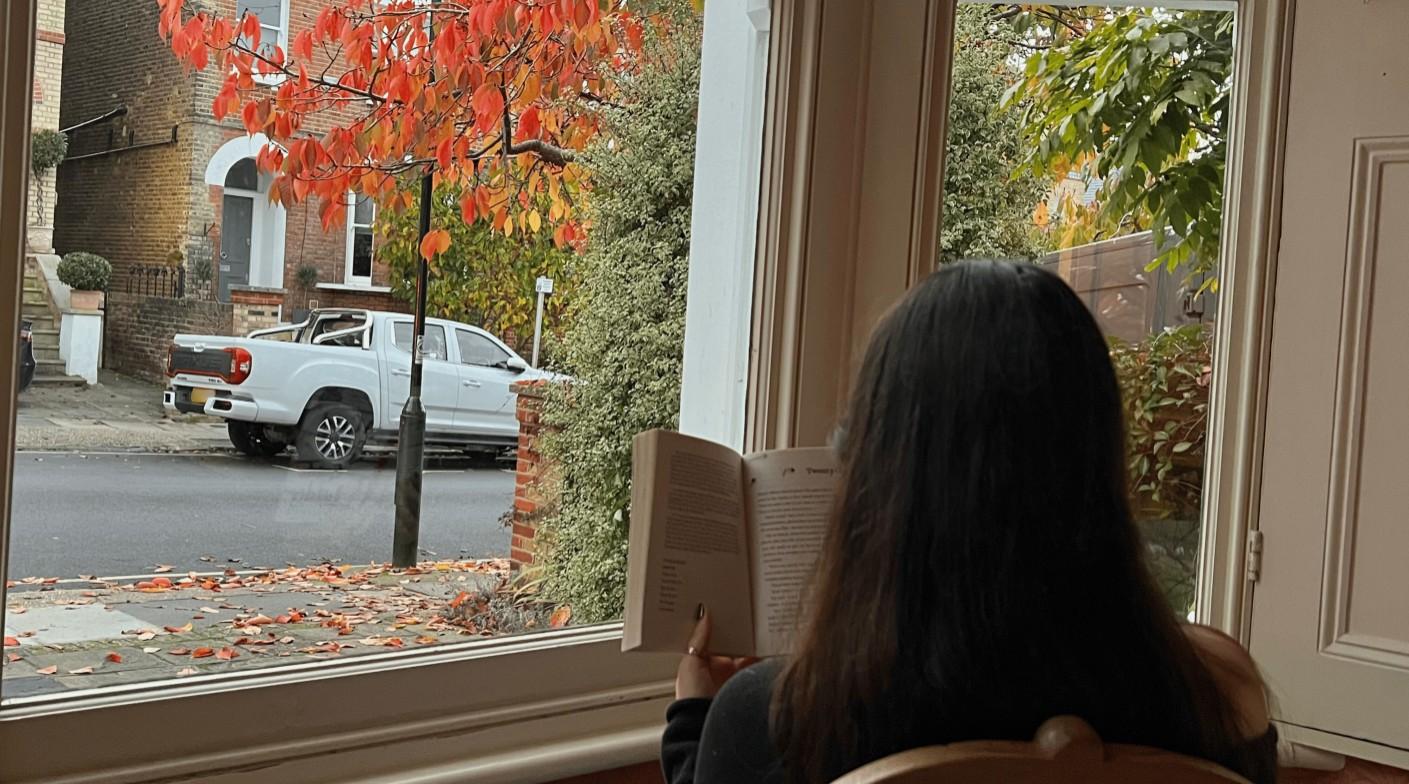

Online reading communities are not confined to the digital space. I’ve seen groups of young girls heading with laser-eyed focus to the ‘BookTok made me buy it’ table at bookshops and gushing excitedly once they found what they were looking for. Such excitement is infectious!

The connection aspect cannot be overlooked. The same research showed that a fifth of those surveyed found a community thanks to interacting with the BookTok hashtag, while a further 15% made new friends this way.

However…

“In the shallow world of BookTok, being ‘a reader’ is more important than actually reading”, declared an article by GQ. This criticism is a popular one, sometimes coming even from within BookTok itself. However, such hierarchical categorisation of readers is detrimental to promoting an engagement with literature. The identity of being ‘a reader’ should be accessible, not exclusive. In the end, it is simply what happens when you pick up a book and read it.

Whether it is a tome by Dostoyevsky, a young adult novel, poetry or a children’s book – if you engage with it, you are a reader and should be welcome in the community. Apart from being snobby, the need to reserve reading as a purely intellectual and critical practice intimidates young readers.

The lively community of readers within King’s College London (KCL) achieves the opposite. Societies such as KCL World Literature, KCL Book Club and King’s Poetry are blooming. So, whether we get our recommendations from our screens or elsewhere, let’s keep this spirit alive.