Staff writer Katie Newman reviews “Emily”, a fictional biopic that shows a life of rebellion and romance, matching Emily Brontë’s fiction.

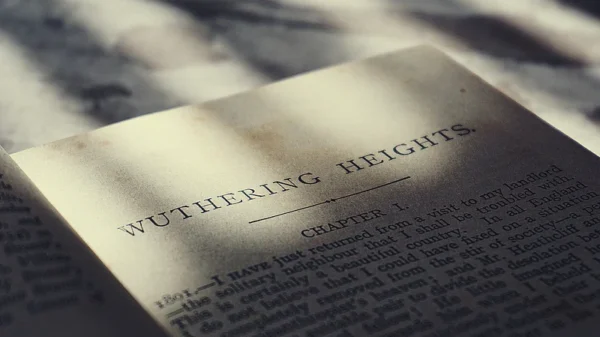

The new Brontë biopic “Emily” begins with the famous author lying prone on a chair, her deathbed. She lies next to her most famous work “Wuthering Heights”, a tale of love, misery and revenge set in the Yorkshire moors, the homeland of the Brontë family. We then travel back to earlier in her life before she wrote her masterpiece and trace her imagined rebellion and love story.

It is important to note that this film is a fictional biopic. While that phrase seems contradictory, the film traces a rebellion and romance that there is no proof Emily had. The film does use the backdrop of Brontë’s real life with her three surviving siblings, Charlotte, Branwell, and Anne, trying to carve out a life for themselves amidst their father, an Anglican priests money troubles. Many of the main events in the film are true such as Charlotte’s being a teacher, Branwell’s addiction and Emily’s place in the background of the family.

The film casts Charlotte as the closest sister to Emily instead of Anne, to whom she was actually the closest. Charlotte and Emily provide interesting doubles for each other throughout the film, Charlotte is the “little mother” who takes the place of the siblings’ deceased mother and tries to guide them in life. She wants to leave Yorkshire and create a better life for herself by teaching yet she constantly keeps up appearances in the neighbourhood to assure that the family is doing fine. While Charlotte represents the accepted role of women in the Victorian period, namely the stereotype of “the Angel in the House” which was popularised by Coventry Patmore’s poem of the same name, it depicted a feminine ideal of a domestic and family-focused woman. While Charlotte does teach, which is a public occupation, teaching young women was seen as a very feminine job and thus wholly accepted by society.

Emily on the other hand is “the strange one”. She longs to be out on the open moors; these are the moments in the film where Mackey’s Emily comes alive. She runs through the grass and heather with no boundaries other than the endless horizon. The partly fictional Emily of the film runs literally wild on the moors. She smokes and takes opium with her brother Branwell, adopting stereotypically masculine pursuits. If Charlotte is the “Angel in the House”, Emily is the opposite of this – she seems to desire the freedoms men like her brother are granted, and thus much of her wildness in the film come from her lack of conformity to feminine stereotypes. The moors, the place of freedom from her restraints as a woman in the nineteenth century, are also the place where she finds love. She initially shares a kiss with Weightman while sheltering from a storm in a ramshackle cottage on the moors. While this relationship probably didn’t happen, William Weightman was a real figure in Emily’s life, being more of a friend of her sisters than a lover of hers. He was also her father’s curate, so it was likely she saw a lot of him.

Weightman initially disliked Emily, seeing her as too vivacious and lively compared to her more docile sisters. He shows his extreme dislike of her when the Brontë siblings and friends, Weightman included, play a game with the Brontë’s dead mother’s mask pretending to be different people. Emily takes this too far as she hears Charlotte and Weightman whispering she is “too shy” to partake and adopts the guise of their dead mother’s spirit, agitating the rest of her siblings and upsetting Weightman with her sacrilegious behaviour. This scene shows the depths of Emily’s gothic soul as she pretends to be her mother coming straight from the “dark”, the place of death and dying and then, after telling each of the siblings and how proud she is of them, the dark comes for her, dragging her back down into the empty and all-consuming blackness. Emily, unlike the other Brontë siblings, seems not to fear death; this is highlighted in her novel “Wuthering Heights” which is peppered with death and hauntings of the dead from the other side.

After Weightman’s anger at her blasphemy, Emily’s sisters travel to a school to teach and study leaving Emily and Branwell free to rebel. They drink, take opium, and rather interestingly go out at night to peek into wealthy people’s houses. Branwell eventually gets caught and ends up having to work as a servant for the people he and Emily spied on. So then Emily is alone, and she goes one last jaunt to peer into the windows of the house and sees Branwell serving the master of the house. This scene is something directly inspired by “Wuthering Heights”, as when Cathy damages her ankle on the moors she is forced to stay with the Linton’s, and Heathcliff is not allowed to visit her so her peers in at her through the windows. The film makes a subtle nod to this scene from Emily’s novel with the naming of the wealthy house owners as the Linton’s.

With no siblings left to spend time with Emily is sent to have daily French lessons with Weightman. She confounds him with more blasphemy, questioning why God gave humans a brain if he didn’t want them to use it and follow him “blindly”. In spending increased time together though, they fall in love. Weightman becomes a sounding board for Emily’s writing, she gives him some of her poetry, they discuss ideas, he gives her the intellectual conversation she was waiting for, and the romance she never knew she would have. While I won’t spoil the ending, their romance is doomed from the beginning much like Cathy and Heathcliff in “Wuthering Heights”.

Mackey melts into the character of Emily. She completely becomes her in the film and encapsulates the spirit of freedom and vibrancy that in the past has only been seen through her fiction. While this film is not completely truthful to Emily Brontë’s biographical context, it imagines for her the life of rebellion and love that she deserved to have, one that matches her fiction.