Culture Editor Jagoda Ziolkowska highlights the paradoxes of learning in today’s world, arguing that overdependence on short-term technological solutions decreases humanity’s long-term prospects.

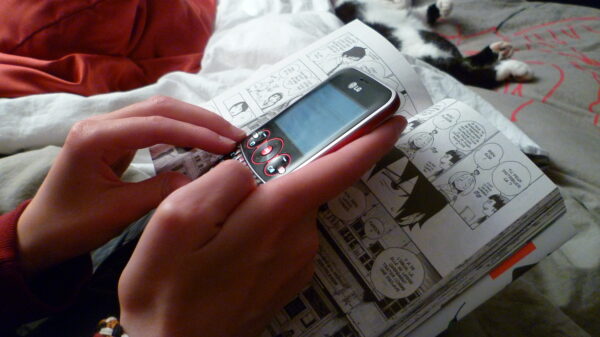

I assume that as you’re reading this sentence, you’re not actively thinking about the fact that you understand the words, but rather focus on what it is that I’m saying (I may be too optimistic: there’s a good chance you’re simultaneously scrolling on your phone). But what if I switched to Polish now? Czy przeraziłaby Cię ilość kresek nad literami, które nie mają dla Ciebie żadnego znaczenia? Confusing, but you could always use Google Translate. Right?

Given we speak English, the dominant lingua franca in much of the world, such instances of consulting a dictionary seem more like satisfying curiosity than a necessity. But in a not-so-distant future, this may well change. The 2024 EF English Proficiency Index report found out that global English competence is in decline. Although the numbers aren’t yet striking, the fact remains: people are becoming less interested in learning the language.

Of course – and as usual – it’s not all that easy. Access to resources is not distributed equally and the command of English in a country is correlated with levels of income, welfare and international integration, among other indicators. Still, for most of us, developing language proficiency has never been easier and cheaper thanks to technology. Countless websites, videos and free online courses not only provide the necessary materials, but also help structure the entire learning process. Technically, all we need to do is just sit down and start.

But whenever motivation comes, the insidious question of: “what for?” follows. And, in all fairness, there seems to be no pressing need. Online dictionaries are ubiquitous. Earbuds translating languages in real time are no longer a sci-fi dream. Why devote tens of hours of your week to memorising vocabulary when taking out your phone is enough to communicate with a foreigner?

Because, to put it dramatically, the very act of learning anything is, in itself, our best bet at survival.

It’s no secret that the carousel we call the world spins so fast that we barely manage not to fall off our seats. What we need though is not stronger muscles; it’s stronger thinking.

Acquiring new skills and seeking stimulating experiences can significantly enhance the brain’s functioning, improving mental faculties and slowing down the age-related decline in cognitive abilities. We badly need this intellectual agility. Despite the common view that information equals truth equals knowledge, it is often the misuse rather than omission of facts that leads to not only flawed, but also dangerous beliefs. With so much geopolitical landscape shaped by the digital realm driven by monetisable impulsive clicks, it goes without saying that staying critical and resisting the oversimplification trap resulting in tribalism, skewed processes of deduction and vulnerability to emotional manipulation is our strongest defence. Yet, the reality is quite different: we rely on technology to solve the problems with our knowledge instead of using our knowledge to solve the problems with technology.

All of this, of course, relates to the elephant in the room: the future labour market. While AI will certainly render some jobs obsolete, humans are unlikely to be left out altogether. Instead, we will need to constantly retrain and assume varied professions, some of which may not even exist yet. Therefore, the challenge will be to master developing skills quickly and efficiently in order to keep up with the pace of emerging sectors. This fact, although widely acknowledged, is rarely followed by the connected pertinent question: how do we do that? We need to know how to learn, unlearn and relearn – fast. And while we can use technology to help us, we can’t expect it to perform our CVs on our behalf.

What a luck then, you might think, that universities so fervently claim to render their students into critical thinkers. But wallowing in the recruitment-friendly perceived ‘analytical skills’ is equally dangerous. Just because you convince yourself that you can think critically, doesn’t mean you consistently do it. To be absolutely clear, I don’t mean we should question every single thing – how bleak life must be when happiness is just a socially-manufactured idea and people are defined solely by their circumstances. Enjoy yourself a little. What I am saying is that seeing criticality as a skill acquired once and for all rather than a continuously practiced habit can lead to complacency and, paradoxically, lack of questioning your own thinking patterns. Insert Descartes’s “Cogito, ergo sum”. (Tempted to now proceed to postcolonial critiques of European philosophical thought? Go ahead. As Fitzgerald elegantly observed: “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function”).

In the end, we all just try to make sense of the world. What we need to remember though, is that while the resources we have to help us do that are abundant, the same is not true for attention and energy. So let’s spend our time wisely. Observe carefully. I do hope you just learnt something new.