The last year has seen a surge of Sophocles in London. From the two productions of Oedipus – announced on the same day – to Brie Larson’s West End debut in Elektra. Notably, all three productions of the tragedies were set in the modern day, and there is good reason to see this as a new pattern in contemporary staging of Greek tragedy. Even as this is written, the National Theatre has just finished a production of Euripides’ Bacchae, with a modern feminist twist. Directors across the country seem to all have the same question in mind: how to make a play, written over 2000 years ago, relatable to a modern audience?

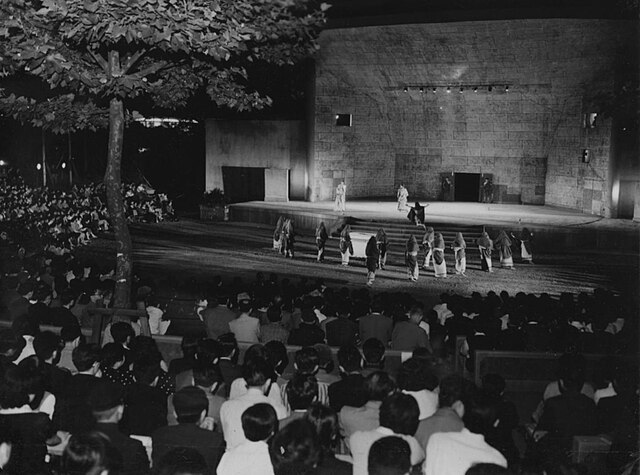

To answer this question, we must compare the expectations that contemporary spectators at West End venues have for a play, to those of a classical audience at the City Dionysia in Athens. The main criteria of a Greek Tragedy are; a relatable hero, a fatal flaw, a moral lesson and a feeling of catharsis. The ancient Athenians would already know the stories they were seeing on stage. It was up to the playwrite to surprise, shock and sicken them.

There was also a religious element to theatre. With the yearly competition of tragedies occurring at a festival of Dionysos, many plays urged audiences not to interfere with the Gods. However, a modern and widely secular audience, may find the message less compelling.

This is perhaps why many productions of these ancient plays are transposing the action to a more modern setting, whether it be a politician’s HQ on election night, or a fragmented modern household. By placing the plays in a time closer to our own, their themes can be more easily understood by a modern audience.

Some productions do this incredibly effectively. Back in 2012, the National Theatre put on a production of Sophocles’ tragedy ‘Antigone’ starring Jodie Whittaker and Christopher Eccleston, set in the office of a modern political leader. In it, Polynices’ attack against Thebes is presented as a terrorist campaign, something that was becoming increasingly relevant at the start of the 2010s, immediately drawing the audience into the play’s world.

A similar idea was presented in Robert Icke’s ‘Oedipus’, one of two productions of the play put on in London within the last year, where Oedipus, portrayed by Mark Strong, is a politician waiting for election results. Icke translates the infamous prophecy of Oedipus killing his father and marrying his mother onto the modern stage. Strong’s Oedipus is subject to political conspiracy theories, and is urged to release his birth certificate; a symbol of the authenticity and origin that are so central to Oedipus’s story.

The National Theatre is well known and regarded for its adaptations of Greek tragedy. In its current production of Euripides’ Bacchae, the focus is on the Bacchae themselves – the women of Dionysos – and themes of feminism and repression echo throughout. Indhu Rubasingham’s directorial leadership amalgamates classic costuming, where layered robes are rusted copper and actors hair is wildly untamed, with a modernised screenplay written by Nima Taleghani. Laden with contemporary wordplay and witty rap, a colloquial voice is given to the tragedy.

However, perhaps it can be argued that in an attempt to modernise, we take away from the original play. Even though there is an attempt to reclaim ‘Bacchae’ as a feminist piece, it is at its heart a story about two men, and perhaps it would be more apt to centre in on the ideas of fate and madness that made the original so compelling. The already existing themes of gender are also ripe for potential interpretation. Dionysos disguises himself as an effiminate man for the duration of the play, while Pentheus dons feminine clothes before his death.

No matter how much of the rest of the play is modernised, there is always one aspect of Greek drama that continues to stump directors: the Chorus. Scholars agree that the Chorus in Greek theatre was a vital part of the spiritual experience of theatre, having evolved out of a prior religious practice.

Nowadays the religious aspect of Greek tragedies has been widely eviscerated – not many people in the modern day believe in the Greek gods, after all – and the Chorus can feel a little odd. There are arguments that the Chorus should be removed in modern adaptations of tragedies. However, there are so many opportunities to utilise the chorus left untapped.

In the production of Oedipus at the Old Vic earlier this year, starring Rami Malek and Indira Varma, the Chorus has no dialogue, instead conveying emotion through dance, accompanied by techno music. The frantic movement to bone-rattling music, loud enough to shake the theatre itself, instilled the audience with a feeling of terror, heightening the impact of the play’s horrifying themes of fate and unwilling incest.

I, personally, disliked the production of Elektra I saw this year, as hearing the word “no” sung over and over again – even in Brie Larson’s voice – can grow rather grating, amongst other reasons. However, I did find the sung chorus to add a freshness to the play, that many other directorial choices sadly failed to achieve. The a cappella harmonies were impeccable, and the composition itself really helped to inject emotion into the scenes. Even the moments of silence between sung lines were timed perfectly to allow the audience to reflect on what just happened.

Combining these is elements of song and dance is the National Theatre’s 2014 production of Medea, which used a combination of frantic choreography and more serene singing to heighten the tension effectively, adding to the focus on Medea’s descent into madness. Helen McCrory’s performance here as the titular character is superb, conveying true heartbreak and rage in the face of abandonment by her husband Jason, as well as her alternating callousness and regret as she murders Jason’s new bride and even her own children. In combination with this innovative chorus, the audience is easily able to empathise with the extreme emotions shown on stage.

Perhaps the takeaway here isn’t that modern adaptations exist solely to make these ancient plays relatable in our modern world. Maybe it simply opens the door to new staging opportunities and explorations of creativity.