Culture Editor Evelyn Shepphird examines political violence and filial loyalty within Robert Icke’s ‘Player Kings’, the West End adaptation of Shakespeare’s ‘Henry IV’ Parts 1 and 2.

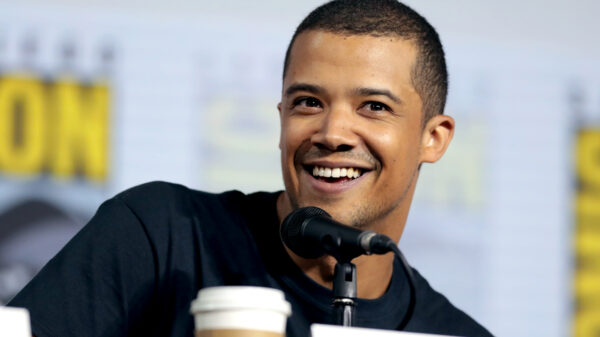

From seedy alleyways rich with robbers to the cold, medieval glamor of Westminster, ‘Player Kings’, adapted and directed by Robert Icke (Judas, ‘Enemy of the People’), brings every face of England to the Noël Coward stage in its tale of political legitimacy, deceit, and honour. Ushered by a graceful, rough-hewn Prince Hal (Toheeb Jimoh) and an unselfconscious, spectacular Sir John Falstaff (Ian McKellen), the play delicately constructs a heartbreaking triangle of divided paternal fidelity in a politically anxious era.

‘Player Kings’, the abridged joint production of ‘Henry IV’ Parts 1 and 2, contributes to the current theatrical ‘vogue’ of British stars playing Shakespeare’s most iconic roles. Just down the street Tom Holland portrays Romeo in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Ralph Fiennes and David Tennant have both performed in ‘Macbeth’ within the past year, and ‘The Motive and the Cue’, a dramatisation of the rehearsal process behind Richard Burton’s 1964 ‘Hamlet’ recently won an Olivier award. With Ian McKellen as the irreverent iconic Falstaff, ‘Player Kings’ is, as Welsh actor Michael Sheen insists, “a major cultural moment”.

Jimoh’s Prince Harry has something of a kept lion in him – his slinking, curled-up ennui covers a capacity for real, threatening strength. This mastery of physicality exemplifies the character. Both blisteringly egoistic and vulnerably insecure, Hal’s lazy confidence around Falstaff burns away into rigidity in front of his father, who aptly warns: “O foolish youth, / Thou seek’st the greatness that will overwhelm / thee”. Before the interval, Hal, who diverts himself with staged robberies and battles of wit with Falstaff, is easily overwhelmed, though not unprepared, for the violent reality of the political sphere. His hair-trigger attitude is well-foiled by Hotspur (Samuel Edward-Cook) and while Hal sheds his adolescent impropriety by the second half, he never really loses his quick temper.

The brutality of maturity makes the second half of the ‘Player Kings’ uniquely heartbreaking. Hal’s ascension as King becomes a violent struggle between him and his dying father (Richard Coyle). During the fight, the King puts Hal in a headlock—later, when Hal carries his father to bed, he is once more put in a headlock. Hal’s reluctance to place the crown on his head is paired with a strange gentleness towards his father – the enemy of his adolescence. The Hal’s final docile obedience to a dying unaffectionate father is both jarring and heartbreaking.

The procession from ‘Henry IV’ Part 1 to Part 2 is in large part the story of Hal’s filial allegiance shifting from Falstaff to King Henry IV. The Prince’s inherited capacity for violence and eventual sense of duty make this a foregone conclusion, but by casting Ian McKellen (‘The Lord of the Rings’, ‘Hamlet’, ‘King Lear’) as Falstaff, this inevitable transition becomes more an abandonment of a beloved paternal figure. McKellen is funny and intelligent in the role – his egregious lies, severe dependence on alcohol and military cowardice is forgivable with his easy affection and twinkling eye.

Sitting in the same theatre as Orlando Bloom and Billy Boyd – the loudly supportive friends and ‘Lord of the Rings’ co-stars of Ian McKellen – it’s hard not to read Hal’s maturing as the complete rejection of a beloved, if inappropriate, knight. This heartbreak is well-designed: the play ends on the image of Hal, dressed in regalia, stepping forward in a pool of golden light. Behind him Falstaff, shrouded in heavy blue light, moves backwards. Thus is the inexorability of Hal’s maturity.

Apparently influenced by the ‘mythic’ self-perception of the United States and the ‘theatricality’ of the Catholic Church, the technical elements of this production are both visually impressive and shockingly minimalist. The modern costuming serves the fight scenes very well, in that it does not shield the audience from the brutality of the production by burying them in the mysticism of history. Thus, violence is not excusable by virtue of its age or adaptation into beautiful, epic poetry. In large part, the fight scenes are horrifying exactly due to the immediacy of the costuming. Furthermore, they support the disrepute of Falstaff’s crew, as the character’s garish, ill-fitting yellow button-down and Hal’s silver chain and leather jacket are effective even if not elegant. However, despite these particular victories, the costuming fails to communicate the precarious, absolute power of kingship. Any ‘Westminster’ figure is poorly outfitted in awful politician-like suits – the King inexplicably spends several scenes in an ugly tweed.

The simplicity of the brick-walled set makes scene changes shockingly quick, a necessity for a play that flirts with a four-hour run time. Once again, Westminster is the victim of this choice – its medieval grandeur is not communicated by the high-ceilinged brick and therefore its sense of stateliness suffers within the first half. Nonetheless, the fact that Hal, Falstaff and, eventually, the true King all sit and pontificate from the same chair in the same location is very satisfying. Furthermore, the set’s minimalism becomes increasingly forgivable as the play progresses: in the second half, there is less of a division between Eastcheap – or disreputability – and Westminster because it implicitly becomes the Westminster of Hal. Thus, it gains a sort of grunge, while Falstaff and all he represents acquires a mysticism by virtue of the second-act introduction of the hauntingly beautiful near-castrato operatic singer (Henry Jenkinson).

‘Player Kings’ seems designed explicitly to communicate the ironic hilarity that surfaces from violent contexts. This is not Macbeth, in which military intrigue becomes a horror story; rather, this bitter narrative of an abandonment of youthful carelessness exhibits humour and brutality in equal measure. The fight scenes directed by Kev McCurdy are terrifyingly merciless, fast and lethal. The choreography leaves a lot of space between the actors as they struggle, probably out of necessity: if any closer, the actor’s quick aggression would draw real blood. For instance, Hotspur’s death is not choreographically framed as a glorious or righteous eventuality. Edward-Cook and Jimoh fight quick and close, and Jimoh’s victory is due to sheer luck rather than skill. The way Hotspur finally dies is nauseating: Edward-Cook is most sickeningly arresting as his body jerks and convulses when he apparently bleeds out. This emetic performance is undercut immediately by Falstaff’s delivery of an ironic monologue.

Ultimately, ‘Player Kings’ is an easily digestible adaptation of Shakespeare’s ‘Henry IV’ Parts 1 and 2. It offers an excellent opportunity to see the perennially talented octogenarian Ian McKellen in a beloved Shakespeare role while making a painful argument about the inevitability of paternal abandonment within the course of male maturity. ‘Player Kings’ feels especially relevant within the absurdity of current political life: the harsh contrast between violence and irreverent humor cleverly directed by Icke builds the entire production around King Henry IV’s claim that “Uneasy is the head that bears the crown”. In an age of anti-intellectualism and crippling political anxiety, ‘Player Kings’ is a comforting reminder from Shakespeare that this is political unease not a unique to our time. This centuries-old constatation ultimately fixes nothing, but perhaps there’s a heartening humanity in this incessant solidarity.

‘Player Kings’ is playing at the Noël Coward Theatre until 22 June 2024.

Evelyn Shepphird is a second year student at King's College London, on the European Studies (French Pathway) Programme.