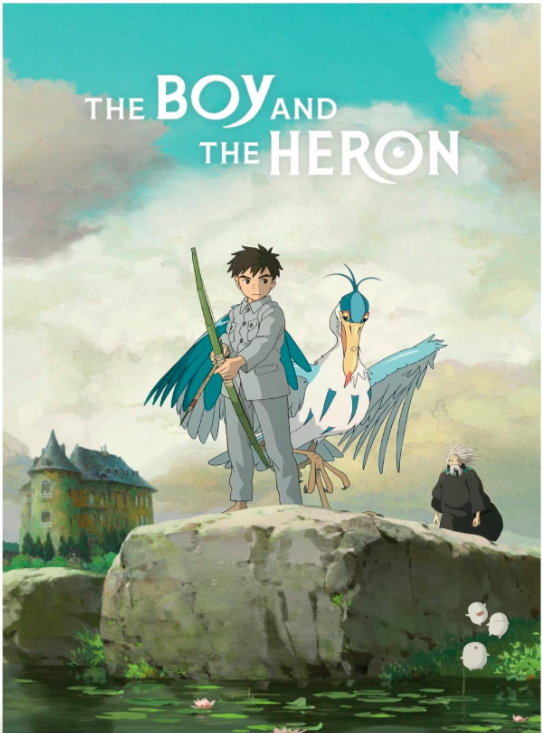

Staff writer Matthew Pellow reviews Studio Ghibli’s The Boy and The Heron

After seven years of production, Studio Ghibli’s The Boy and the Heron premiered in the UK on 26 December 2023, having hit Japanese cinemas in July. Studio Ghibli is one of the leading animation studios in Japan. In this case, their unconventional marketing approach of “doing nothing“, aside from publishing a single hand-drawn poster, appears to have paid off, with the film grossing over $162 million at the box office worldwide, surpassing the opening record, for the company, previously set by Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). The film was also well-received by critics, making Golden Globe history by becoming the first non-English title to win the award for Best Animated Feature.

Much of this success can be attributed to the winning combination of the prolific ‘three musketeers’ of Disney-independent animated cinema, Joe Hisaichi, the musical director, Toshio Suzuki, the producer, and Hayao Miyazaki, the director and writer. In an interview, Suzuki said the film “cost more to make than any other movie ever made in Japan” and took double the time of other Ghibli entries. With the freedom of production without time and budget constraints, The Boy and the Heron features some of Ghibli’s most beautiful art, reflected in the intricacy and scale of the exquisitely animated world.

But The Boy and the Heron is not just another Studio Ghibli film. Miyazaki announced it will, probably, be his last. It is fitting that Miyazaki’s last film is his most autobiographical.

Following the formula of magical realism set in titles such as Spirited Away, The Boy and the Heron begins in Tokyo under heavy bombardment during the Pacific War, the time period in which Miyazaki grew up. The story follows Mahito, a young boy who struggles to adjust to life in a new town after his mother’s death. When a talking heron informs him that his mother is still alive, he enters an abandoned tower in search of her, transporting him into a fantastical alternate world. Parallels with Miyazaki’s own childhood can be seen throughout the plot; his family fled Tokyo for the countryside in 1944, where his father worked in a fighter plan factory, instilling a fascination for aeronautics in the young Miyazaki which would inform his later work. In addition to similarities in the storyline, the greater themes of loss, war and loneliness reflect Miyazaki’s early life – punctuated by the Second World War and childhood health problems which made him feel like an outcast.

In addition to his own childhood, Miyazaki drew from Japanese fiction in the writing of the film. The Japanese title for the film poses something far more philosophical than the English; ‘How Do You Live?’. Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel by the same name shares some similarities with the plot of the film, with the protagonist losing his father and subsequently growing closer to his uncle, however, Toshio asserted Ghibli “only borrowed the title”.

Despite this fact, themes of mortality and loss in the book are certainly mirrored by the film. At 83-years-old, such questions are particularly pressing for Miyazaki. As with many of his other works, most notably Princess Mononoke (1997) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), characters explore the difficulty of maintaining a humanistic ethic in a violent world. Particularly powerful, however, is Mahito’s choice to return to the real world despite the loss of his mother, giving up the chance to continue the work of his great-uncle and engineer a world in his own image.

While the animation in The Boy and the Heron was particularly strong, the storyline of the film lacked some coherency in the second half. Likewise, Hisaichi’s soundtrack failed to deliver any songs to be remembered. However, though the original score does not have quite the same impact as some of Ghibli’s other titles, such as Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), it collaborates well with the animation. There is a masterful use of silence notably in the first half of the film, a clear collaboration in the vision for the film between Miyazaki, Suzuki and Hisaichi. This simplicity in the soundtrack renders the animation more immersive in the slow-moving first half of the film, but occasionally undermines the plot in the more action-packed scenes.

While elements of the film did not live up to expectations, it is nowhere near Ghibli’s weakest film in recent times. The Earwig and the Witch (2020), directed by Gorō Miyazaki, son of Hayao Miyazaki, received crushing reviews from critics, described as a “near-total misfire” for Ghibli on Rotten Tomatoes. The first feature he produced without his father’s assistance, such poor reviews do not bear well for his future in succession to his father at Ghibli. It is no wonder then that Gorō refused to take over as leader of Ghibli.

But will Miyazaki really retire from making films? Miyazaki first announced his plans to retire in 1997, after the release of Princess Mononoke (1997). Periodically, since then, he has announced his retirement a total of four times, only to return to work a few years later. In 2013, Miyazaki said at a press conference, “I feel that my days in feature film are done,” and that “if I said I wanted to [continue], I would sound like an old man saying something foolish”. In spite of this statement, he returned to the Studio in 2016 to produce The Boy and the Heron.

This time it appears more likely. Despite the fact it has been reported that Miyazaki is working on ideas for new work, given that The Boy and the Heron took over 7 years to produce, it seems unlikely the 83-year-old will be able to produce another.

In October 2023, Studio Ghibli was acquired by Nippon TV after no successors were found for Miyazaki. While both Suzuki and Miyazaki remain on the board of the Studio, taking the roles of Chairman and Honorary Chairman respectively, they are no longer in management positions. The cited reason for Suzuki and Miyazaki stepping back is their advanced ages making continued work more difficult. As Suzuki and Miyazaki pull back from work at Studio Ghibli, none of the original members of the Studio remain. The third co-founder Isao Takahata, perhaps best remembered for his last film, the Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), passed away in 2018.

Miyazaki said of Studio Ghibli in a 2013 documentary, “the future is clear. It’s going to fall apart. I can already see it. What the use worrying? It’s inevitable.” If Miyazaki is right, it could spell the end of an era for both Japanese cinema and independent animation alike. Commentators argue that if the Studio shuts down, it will create a monopoly in the industry for Disney; smaller studios simply do not have the resources to rival the behemoth. There is also a worry that Ghibli’s traditional approach to animation will also fall by the wayside, given the technological advancement associated with Disney’s animation.

Regardless, Miyazaki’s work has left an indelible legacy on animation as a form of art. Helen McCarthy, author of Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation, noted Miyazaki’s influence on a plethora of contemporary artists in an interview, “Western artists [have been] inspired by Ghibli work in ceramics, video, theatre, and music as well as painting and graphics”. In this way, Miyazaki has brought new life through his work to the independent animated film industry. While The Boy and the Heron may not be Miyazaki’s strongest movie, overshadowed by earlier entries such as Spirited Away, it remains a beautiful and deeply moving film, certainly worthy of being Miyazaki’s last.