Roar writer Dania Quadri reviews Shoreditch’s art exhibition, The Stars are Bright.

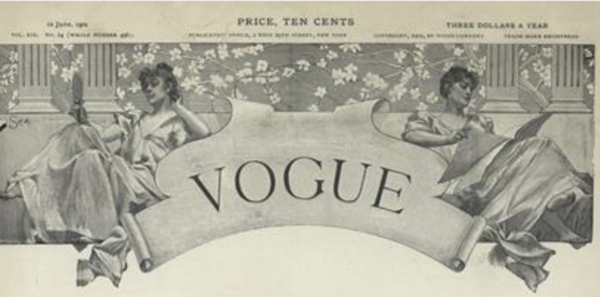

The Stars are Bright is an exhibition in hipster central Shoreditch that displays watercolours from the Cyrene Mission School, Zimbabwe in the 1940s. Presented by The Belvedere Trust and curated by Georgia Ward, Chiedza Mhondoro and Jessica Ihejetoh, the exhibition runs until 31 October 2020, after which the Collection will tour Zimbabwe for the first time since the 1940s.

As soon as I stepped through the glass doors, I identified two key aims of the curators. First, to make the exhibition accessible to all, and second, to celebrate the work of Black artists. Both these aims fed into each other; since the exhibition was accessible, it in turn enabled the audience to engage deeper with the artists. Moreover, the exhibition was free so those who may not otherwise be able to attend expensive art exhibitions were able to do so. Additionally, the event was step-free and audio was available to those who needed it.

Equally significant was the connection the audience was able to forge with both the artworks and the artist. A simple instruction relayed to us by friendly stewards enabled this: to follow the star stickers on the floor to navigate this gallery. These stars were borrowed from the artwork used to name and promote the exhibition; The Stars are Bright by Musa Nyahwa.

From the get go, I felt like I was being encouraged to explore the artworks. While the stars lead us through our timestamped journey, the plaques provided some context to the work and the nature sounds interspersed with the xylophone and triangle reminded me of a tune that would accompany a movie about a fantasy land.

A younger me used to walk into art galleries and obsess over things like how the work was meant to be acknowledged, where to start in the gallery, where to end, what the point of it all was, and whether there was one at all. The curators of The Stars are Bright circumvented these issues well. You did not need an artistic background to be here.

A River in My Country 1945, George Kachange

Most of the artworks contained elements of nature – boulders of varying shades and colours, trees and other shrubs, a river and the depiction of life in Bulawayo. I thought the works were based on students’ own experiences of their life, and how it changed in the 1940s.

The Cyrene Mission School was started by Edward Paterson, a Scottish clergyman who was keen on disseminating the teachings of Christ, and encouraged pupils to relay their understanding of Christianity through an African lens. But if this was the main aim of Paterson, I found it most strongly reflected in The Good Shepherd by Livingstone Sango.

The Good Shepherd 1945, Livingstone Sango

Here, Christ is dark-skinned and surrounded by the wildlife and nature that were present in other artworks too. The story of Christ is presented as an African story – one bereft of Western influences. This is as redeeming as it is refreshing. Interestingly, no two trees are painted in the same colour. This vibrancy conveys both magic and joy, emotions invoked when a disciple remembers Christ.

Other works were similarly colourful, and I was constantly drawn to the multicoloured boulders that were present in nearly all of the paintings. These boulders seemed to be a unifying element across the works. Alluding to Zimbabwe’s rocky terrain, this was also depicted by the curators through a wall cut out to resemble a plateau on which other artworks were displayed, harmonising the artworks with the physical space they were hosted in.

The Theatre Courtyard Gallery, Shoreditch

Before taking the time to read the plaques, I threaded the artworks together to formulate my own story. My thesis was related to the students’ interpretation of imperialism and the Christian Mission. It appeared that when the main subject of the paintings was white missionaries, the nature that was otherwise brightly reflected appeared dull and less magical. These paintings documented change.

Equally, when a poster indicated that at that timestamp black teachers now began teaching at the school, the artworks were bright and colourful once again. Focus was less on depicting European elements such as a hunter in khaki shorts, white Christian missionaries with their bags, religious head-wraps and midi skirts, now Zimbabwean nature and preoccupations regained the limelight.

Or, this had something to do with time’s effect on paint and paper. It may not have been the story the curators intended to convey, but one that I projected on to the works as a means to engage with them. This was telling of my own assumptions about both Zimbabwean culture and the students’ experiences.

Artist and title unknown

John Vuvuya, title unknown 1944

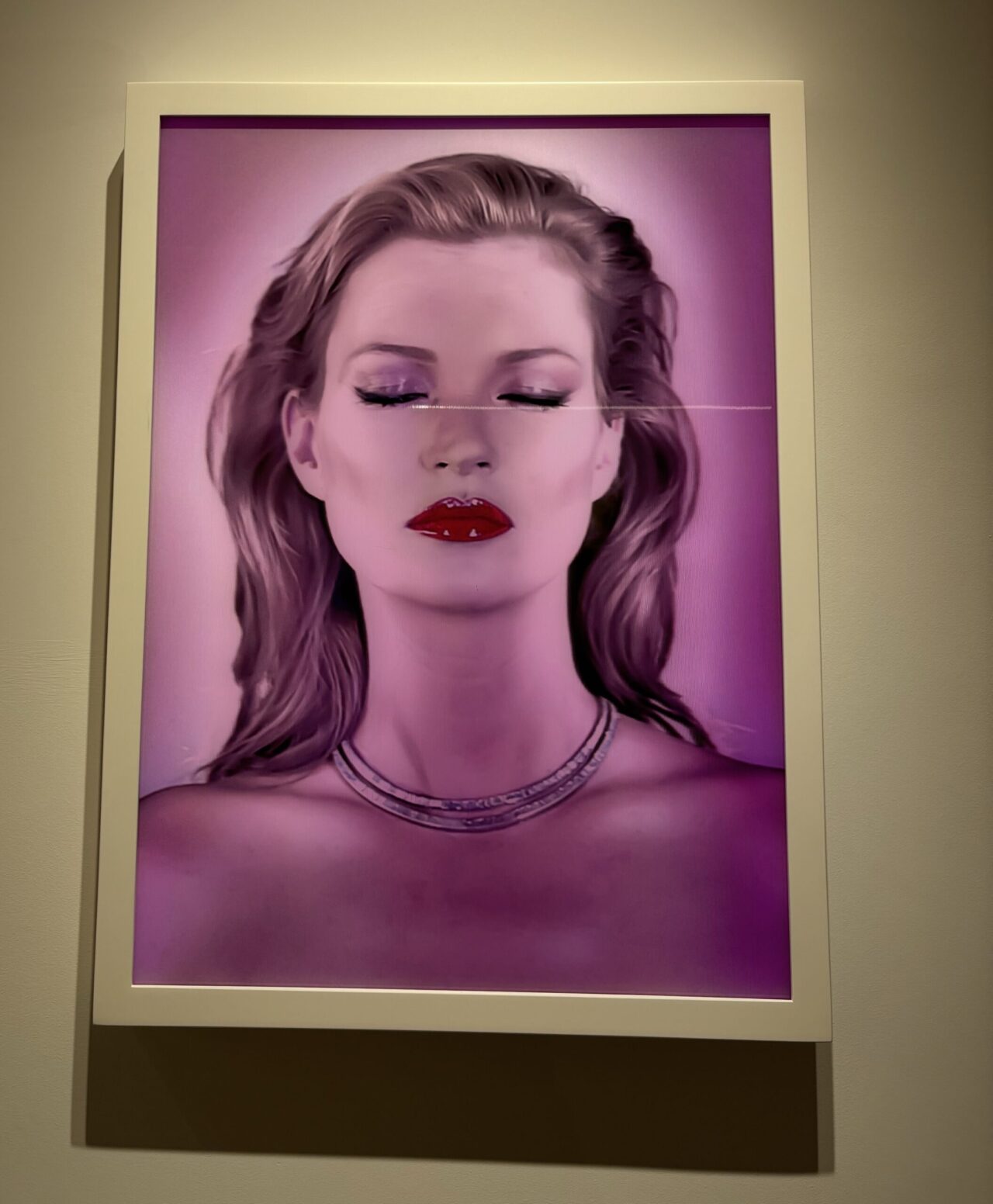

Aside from pondering over how my own biases projected on the works, the exhibition left me questioning the accessibility to art, and how appreciation for art may be inculcated. One way it was done in The Stars Are Bright, was to instill a connection between the audience and the artists. Unlike The Head of a Man, the figures in The Stars are Bright are created through a Black lens and the artists names are rightly venerated.

Today, the contributions Black people have made to art must be celebrated by exhibiting more work by Black artists. Indeed, artworks promote the connection between varied communities with the medium of art, deepen their engagement with it and invite them to be a part of it.