All images are courtesy of Natalia Georgopoulos, 2025.

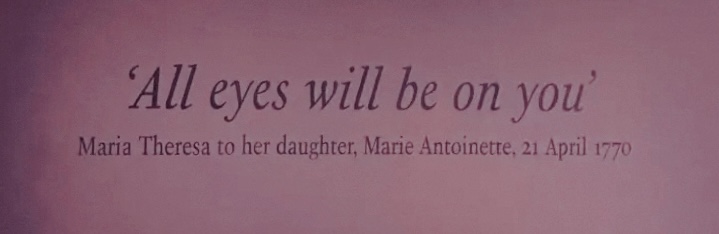

“All eyes will be on you”

These words, that Maria Theresa spoke to her daughter, Marie Antoinette, open the exhibition. Immediately viewers are captured, as all eyes are turned on the 18th-century Queen. Marie Antoinette Style is an expertly crafted and insightful exhibition, that takes visitors on a journey through her life. Moving from her prestigious beginnings, to her tragic end, and following the continuation of her legacy into the 20th and 21st century. Curated by Sarah Grant for the V&A, the exhibition is a lens into how the young fashion icon paved the way for the modern day ‘influencer’.

The start of her Style

The exhibition commences with her wedding dress in the centre of the room surrounded by other garments evoking “the styles Marie Antoinette popularised”. The dress is a magnetic beauty, its presence commanding attention. Amidst the shimmering embroidery of the dress and the train, that would accompany her down the aisle towards Louie XVI, the small bodice reminds viewers that she was married at only 14.

The Austrian heiress’s style invited discourse throughout her reign. A plaque placed opposite her wedding dress reads “every aspect of [her] dress and appearance was scrutinised, discussed and copied”. This is instilled in visitors minds as they continue through the gallery.

Elegant ballroom gowns are accessorised with masques and adorned with pearls, whimsical floral detailing and ribbons. Loungewear is made using the softest cotton to contrast the formal wear. Travel dresses are tailored with hoods and detachable sleeves to provide the queen comfort during her travels. In all their detail, each garment stands plainly within a simple glass case. This very simplicity accentuates the intricacy of each symbolic motif, in all their bows, beauty, and craftsmanship. Allowing visitors to admire these details creates a room that embodies the idea of ‘every girls dream’. Each garment crafts a different story, with the walls providing detailed visual guides to accompany the experience.

Each look carried power, dominance and distinct identity with it. Robe à la Polonaise, or ‘gown in the Polish style’, and the French equivalent ‘Robe à la Française’ were informal styles that became fashionable in the 1770s. Marie Antoinette, being at the forefront of fashion, embraced this. The gowns had a hood attached and detachable sleeves, based on the informal German travelling dress.

Among artefacts presented, was her wardrobe book, ‘Gazette des atours de Marie-Antoinette’, featuring a handful of the 101 silks, which were specifically ordered for and given to her in 1782, allowing the young queen to choose the patterns of her formalwear. The most prominent gown, incorporating silk, is a sparkling salmon satin dress, embellished with faux ermine fur. Ermines symbolized royalty, power, wealth and purity due to their expense and rarity. The purpose of the embellishment on the dress was to mimic real ermine fur, providing clever visual trickery. This element in fashion was favoured amongst court gowns within the time-period. The sample book displays the same pattern in shades of duck egg blue and ivory. Browsing the palette of pastels, one is transported into the mind of the queen; an insight into the luxury of choice, not afforded to the French citizens she ruled over.

Within the walls of Versailles

Aside from royal duty, Antoinette enjoyed curating her private retreat. “She made her mark on the Palace of Versailles at the Petit Trianon, which became the centrepiece of an elegant and unaffected style”. The exhibition leads you by the hand, through a day of landscaping the garden, walking in the French countryside, rearranging, and then redesigning, the furniture and immersing oneself in music – much like Marie Antoinette would, herself.

One piece in the exhibit is Marie Antoinette’s armchair. Designed by Jean-Baptise-Claude Sene, and painted and gilded by Louis-Francios Chatard in 1788, her armchair, which was one of four, stood royally; Poseidon in the sea of turquoise it ruled over. The decedent gold hardware features intricate carvings of motifs including wreathes, crescent moons and portraits of Diana of Versailles either side of the arms. Diana, in Roman mythology, is the goddess of hunt, the moon and nature. The medallion on the top is engraved with ‘MA’, Antoinette’s monogram. ‘Her preferred shade of violet’ accompanies the white cotton with floral detailing.

Queen Toile De Jouy

Following her partnership with ‘Toile de Jouy’, a type of French textile featuring romantic, pastoral landscapes, she was granted the eponymous nickname “Queen Toile de Jouy”. Fabrics that filled her interior and wardrobe, draped with elegance on display. They depict flourishing natural scenes of animals hard at work or scavenging amongst flora and people set up in scenarios where some are enjoying music and some playing ball games. Lovers held each other on tree stumps with their dogs laying by their side and a goat carrying their trinkets. Each picture is telling a different story of how people utilised nature to pass their time. Antoinette incorporated designs “which celebrated the rural industry of France”, allowing her to idolise the view of the French countryside using “scenes of courtship and romance”.

The contrast between her idealisation of the French countryside and her way of life there were simultaneous. She enjoyed solo walks through the gardens where she would design landscapes, small gatherings with friends and overseeing the farm which generated fresh produce. These activities portrayed onto fabric so beautifully, contrasted the life ordinary townspeople of lower classes were living simultaneously. An insight into why the public began to resent and protest Antoinette began to unfold.

The Queen’s Hamlet, designed by Richard Mique, featured a picturesque model village featuring thatched-roof buildings, a house, a working farm and an artificial lake. Built in 1738, The purpose was to create a haven for Antoinette where she could step away from strict court life and live a more simplistic lifestyle, allowing her to connect with nature. She enjoyed using the grounds for privacy, to educate her children and to host events.

An interactive element was successfully brought into the exhibition by showcasing a collection of scented perfumes within ‘portrait busts’. Each bust was infused with fragrances inspired by the scents within the queen’s world. Featured are scents such as ‘Masquerade Ball’, ‘The Queen’s English Garden, Petit Trianon’, and even ‘Conciergerie Prison Cell’, which has scent notes of “mildew, cold stone, sewage, river, juniper”. It is said that Antoinette asked her jailer maid to burn juniper in order to mask the air within her prison cell.

Being able to smell each scent immersed viewers into a glimpse of her world and the shift from the fragment lilac and honeysuckle to the sewage and river allowed us to see the drastic turn of events from the sweet life to the more sinister. Antoinette created scents using a perfume burner, created by Perrie Gouthiere and Francois-Jospeh Belanger. The burner became a staple in the queen’s life, so much so that they began to appear as decorated elements within her interiors.

The Wicked Queen

The 1780s was a time which saw France struggle as a country socially and financially. Louis XVI’s government faced bankruptcy due to the nobility and clergy being exempt from tax. This system burdened those in lower classes whose incomes were being used to pay for the tax debts which accumulated. The social inequality drove those in poverty to riot for the unfairness. Progressively, the situation worsened as people were not earning far enough money to even accommodate themselves alongside the debt. The monarchy was abolished in 1792 by the National Convention, the first French government who were organized as a Republic. The party sentenced King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette for treason and conspiring against the state. Throughout the financial crisis, Antoinette’s lavished spending persisted, angering the public.

Following the exhibit, you find a smaller space titled ‘The Wicked Queen’. As the political unrest of the 1780s swelled, the public grew unhappy with the life of opulence led by the monarchy. Soon, Marie Antoinette began to be depicted as a “wicked, monstrous creature” who “engaged in scandalous acts”. Journalists, artists and authors flocked to tarnish the Queen’s image. Writing articles and producing art, with the intent to obscure opinions of her, the pejoration of her image spread like disease. Marie Antoinette was now the queen out of touch with her people.

Following the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, “her style was condemned as a symbol of royal excess”. Here, in the gallery, visitors’ wide eyes shift to furrowed brows, as the room takes on a sombre mood.

The walls are no longer ornate with art, but with propaganda used to “[portray] her as an enemy of Republicanism”. They “frequently depicted her in animalistic guises imbued with misogyny.” The coquette, whimsical fashions which embodied the youthful, outgoing queen in shades of pastel, were now shadowed by the anthropomorphic, crude and sexualised interpretations of her.

in 1791 the royal family attempted escape to Montmédy. Ultimately futile, however, it only escalated the pejoration of the monarchy’s image, as they were caught and arrested in the small town of Varennes, before they could reach their destination. The room is more sombre still, as visitors anticipated her tragic end.

The End of her Reign

“Everything that ends her torture is good”

Writes Maria Carolina, Queen of Naples, on the possible fate of her younger sister, Marie Antoinette on the 6th of October 1793.

This quote is showcased on the maroon-tainted walls. It is a very poignant element throughout in the next part of the exhibit, with the blood-toned red of the walls both darkening the room, and representing the violence and gore of her inevitable execution.

On the 14th of October 1793, Antoinette was found guilty of treason, and publicly executed. She was stripped of the identity she had created for herself, arriving in 1792 in a creased white chemise. The plain linen contradicts the wardrobes of silk, satin, gemstones and feathers seen at the start. The room was drowned in melancholy. Smiles and giggling conversation gave way to hushed sighs and sorrowful glances. Expressions of wonder and fascination became those of head-hung mourning. As a visitor myself, it was difficult to process this part of the exhibition.

To see her ornate lifestyle though glimmering fabric and bows overshadowed by her bleak, violent end was distressing. Dying at just 37, How much of the world was she aware of? Did she know of the growing resentment towards her outside the castle walls?

“Nothing can hurt me now”

The words of Marie Antoinette, in August of 1793, concluded this showroom.

Antoinette’s Influential Era

Following her death, Marie Antoinette was memorialised amongst the middle class. Led by Empress Eugine of France, ‘royalist sympathisers’ continued to preserve her legacy throughout the 19th century. Aristocrats donned costumes of the late queen at fancy dress balls, and she inspired younger generations of princesses to host parties infused with her style. English Royalists adopted her as a character; the most notable displayed in the exhibition being Daisy Greville, the Countess of Warick, who dressed as Marie Antoinette to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

Featured alongside photographs of the many rooms and surrounding areas that make up the Palace of Versailles, there is a portrait of the countess Eugine wearing a grand ballgown, decorated with eye-capturing fabric and trimmed with ruffles and accessories iconic to Antoinette’s style. Photographs from Empress Eugine’s own masquerades, adopted from Antoinette’s love for attending them, also lined the walls.

Antoinette Reborn and Restyled

The final section is breath-taking beautiful, and the visual appeal truly created one of the most perfect room-setups an exhibition has displayed. This unforgettable array of designer dresses and shoes draws attention to Antoinette’s ‘rare combination of glamour, spectacle and tragedy’, reflecting how Antoinette ‘had become an eternal cultural muse – forever in vogue, forever reimagined’.

2006 saw Sofia Coppola’s Oscar-winning film, starring Kristen Dunst who plays Marie Antoinette. This brought forward costumes designed by Milena Canonero and Manolo Blahnik’s iconic hand-made shoes which were crafted in a way which ‘captured the essence of the queen’s shoe collection’ and followed 18th-century shoemaking techniques.

Each shoe is exceptionally beautiful in its own unique way, and the striking colour and embellishment made it wonderfully difficult to move on from this display. The creativity remained endless as the journey through dresses developed in extravagance.

A handful of talented and respected names in the fashion industry such as Christian Dior, John Galliano, Karl Lagerfeld and Vivienne Westwood are set forth to be admired and adorned. Distinguishing which elements influenced designers in their work after encountering the life of Marie Antoinette on a personal level was fascinating.

Witnessing the wardrobe throughout the exhibition allowed viewers to recognize elements embedded within the restyled collection such as the ‘delicate tiers of silk trimmed with lace’, (Maria Grazia Chiuri for Christian Dior Hature Courture, 2003) and the “striking panierd silhouette and romantic train” that “are reimagined through a contemporary Valentino lens, evoking femininity and Trianon aesthetic synonymous with the queen”, in the piece by Alessandro Michele for Valentino’s Haute Courture collection of Spring 2005. The playful and confection-esque gowns created by Jeremy Scott for Moschino in 2020 using silicone, drew inspiration from the ‘18th-century Boucher-esque scenes.” They were given the name “Let them eat cake”, a phrase associated with Marie Antoinette during the French revolution, said to symbolize how she viewed the contrast between aristocracy and those living in poverty. These were crafted excellently, with both dresses conveying a two-tiered cake effect and embodying the youthful life Antoinette lived.

“We have dreamt a pleasant dream, that is all”

Were the words of Marie Antoinette in spring 1793. This is the last quote, as the exhibition comes to an end, leaving one to reflect on the possible appearance and reality of what has been witnessed. The dream-like elegance of the life she lived in contrast to her final years are something to reflect on whilst we are provided with an essence of closure, reminding us that Marie Antoinette was, perhaps, aware of the element of surrealism to her lifestyle.

I highly encourage you to visit this exhibition, running until the 22nd of March 2026 at the V&A South Kensington and experience the journey through the 250 years enriched with history, fashion, art, lifestyle and culture. You are truly captivated from the moment you walk in.