Student dropout rates appeared to have risen over the last five years, according to data from the Student Loans Company (SLC).

Figures from the SLC indicate that the number of students who applied for a loan before dropping out has risen by 28%, from 32,491 in 2018-19 to 41,630 in 2022-23 – an increase of 9,139.

At the same time, the number of students enrolling in university rose by 11% between 2018-19 and 2021-22. Between 2020-21 and 2021-22 alone there was a 4% increase in the number of students enrolled in Higher Education (HE) institutions in the UK.

As to why the dropout rate has increased, there are several potential factors. A recent study led by the Policy Institute at King’s College London (KCL) and Transforming Access and Student Outcomes in Higher Education (TASO) found that in 2022-23 students were 25% more likely to cite mental health as the main reason given for undergraduates considering dropping out of university, compared to the other options available on the survey.

Financial difficulties was also another popular reason given. Figures from the Department of Education (DfE) showed that in 2020-21, 95% of those eligible took up a student loan.

Furthermore, full-time undergraduate HE students who began their studies this academic year are, on average, expected to borrow £42,100. However, only 27% of these students are expected to repay their loan in full.

Current maintenance loan rates also do not account for the sudden increases in inflation brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine as annual increases are calculated based on out-of-date projections. As such, there has been a “significant real-terms cut” to maintenance loans since 2020-21 of around £1500, according to Russell Group.

Disrupted learning due to the Covid-19 pandemic and continuous waves of strike action could also factor into this increase in non-continuation.

A DfE spokeswoman said that it was taking “firm action to crack down where there are disproportionately high dropout rates across higher education.

“We are asking the Office for Students to impose recruitment limits on courses that are delivering poor outcomes for students, including low earnings and poor job prospects, to prevent the growth of low-quality courses.

“This will help to curb early withdrawals, by giving students confidence that their course will equip them with the skills they need, whatever route they choose to take.”

Comment and Analysis by News Editor, Imogen Dixon

The comment from the DfE spokeswoman seems to imply that limiting recruitment to degrees that have poor financial and career prospects is at the heart of this steep increase in the number of students dropping out of university.

Yet the findings of the KCL Policy Institute and TASO’s study paint a different picture. They also seem to imply that mental health and financial difficulties go hand in hand. Students who relied on either a maintenance loan or grant, or paid work, were more likely to have mental health difficulties compared to those who had received scholarships or had support from their family.

The past few years have seen an exponential rise in the cost of living. House hunting in London increasingly feels like looking for a needle in a haystack, and as winter looms many return to layering up instead of turning on the heating in their exorbitantly priced flats.

The Policy Institute and TASO have stated that “what [they] have found is cause for concern”, as the number of students who have been identified as having a mental health challenge has nearly tripled in the last six years, from 6% in 2017 to 16% in 2023.

“Even allowing for a changing understanding of, and an increasing openness about mental health […] the timescale being described […] suggests that many thousands of students are experiencing substantial distress, and that this has risen dramatically in recent years.”

The report acknowledges that this increase in poor mental health amongst students, whilst undoubtably affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, predates both events and as such cannot be explained away by them.

The question that remains then, is whether students receive sufficient support from their universities. When it comes to King’s, the answer is unclear.

Although the College continues to provide hardship funds, many students have said that there is a lack of clarity with regards to what extra funding is available, and who for. In addition, lengthy and often complicated application processes result in many not applying for them at all.

Data from the Office for Students indicates that both continuation rates (where a student completes at least one year of study) and completion rates (whereby a student completes their studies) are lower for underrepresented groups. As testimony has shown, King’s could be doing more to support students from these groups.

If the DfE is attributing high dropout rates to courses delivering poor future outcomes to students, then it is worth wondering which degrees, and which universities, are likely to be targeted in the “crackdown on rip-off university degrees”.

Aside from a demonstrating general disdain towards Arts and Humanities degrees, this ‘crackdown’ will threaten the social mobility of students from low-income backgrounds.

Research from the Institute of Fiscal Studies in collaboration with the Sutton Trust found that “universities sometimes seen as having lower graduate outcomes are in fact contributing strongly to social mobility as their students from low-income backgrounds go on to earn more highly than they otherwise would have done”.

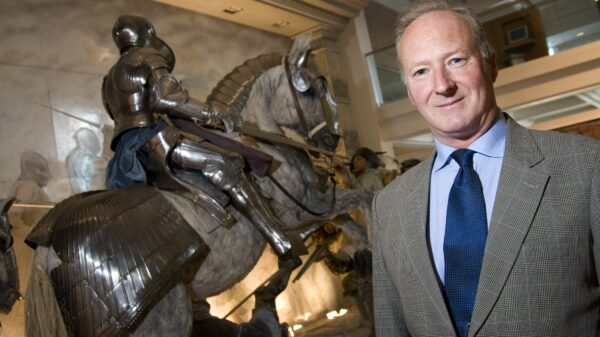

Founder and chair of the Sutton Trust, Sir Peter Lampl, added that “less selective universities are really doing the heavy lifting to promote social mobility.”

Moreover, for many students, doing a degree is not simply about finding a high paying job at the end of it. Most students undertaking ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees understand that a pot of gold is not waiting for them at the end of their walk across their graduating stage. It is a love of their subject that drives them – although maybe not to every 9am lecture.

So, rather than doing away with degrees people do because they love their subject as an attempt to curb dropout rates, universities (and the government) could look at how better to support their cohort mentally and financially. Lord knows we need it.