Roar writer Hannah Apen explores complexities around freedom of expression, cancel culture and the limits of our liberty.

A conversation which never strays far from the limelight has once again taken centre stage. The stabbing of Salman Rushdie in New York fuelled an outcry amongst writers, human rights advocates and ordinary citizens. Through an attack on one man, our collective liberty is threatened. Do we not deserve to express our views without fear of violence? Is it not a fundamental entitlement to be free to say what we think? And what does it really mean to enjoy freedom of speech?

Who is Salman Rushdie?

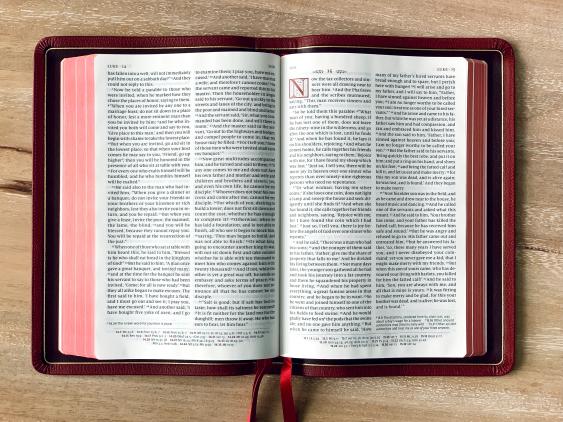

Salman Rushdie is a prominent author who rose to fame following the publication of his 1981 novel ‘Midnight’s Children’, for which he was awarded the Booker Prize. His 1988 work ‘The Satanic Verses’ is the subject of widespread controversy and has sparked vehement criticism from opponents. Rushdie’s surrealist novel explores the experience of immigrants travelling to the UK. One sub-plot challenges a central Islamic belief that the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was entirely innocent and free from sin. In the novel, Rushdie refers to a pre-existing and contentious tale in which Muhammad is deceived by the devil.

Scholars have debated the historicity of this legend for centuries, leaving the subject controversial within many circles. In recent times, followers of Islam overwhelmingly reject the story’s authenticity, and consider Rushdie’s presentation of it to be gravely blasphemous. As well as entertaining the notion of the so-called ‘satanic verses’, the names of Rushdie’s characters inspired outrage. From an unflattering, historically and scripturally loaded rolodex, the cards that have caused the most offence are those of three prostitutes bearing the names of Muhammad’s wives, who in Islam are considered the mothers of faith.

‘The Satanic Verses’ was banned in several countries, faced legal challenges and protests in the UK and earnt Rushdie a fatwa from the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran. This is a religious decree calling for his death, which forced the author into hiding. The fatwa has not, to date, been revised or revoked. Alongside the attack on Rushdie this year, those associated with the novel have faced violence and harassment across the globe. An Italian translator was stabbed, a Japanese translator was murdered in his university office in 1991, and a Norwegian translator was shot outside of his home in 1993, among other incidents.

What does it mean to be free?

Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. This is usually taken to encompass freedom of opinion, religion and thought. Considering its absence conjures Orwellian images of oppressive, totalitarian regimes, unhinged dictators and civil unrest.

But all freedoms have their limitations. Freedom is a concept which philosophers have grappled with for centuries. From Aristotle to Nietzsche, many have said their piece and attempted to define and analyse the notion. Few agree.

There are of course circumstances where freedoms conflict with one another. The need to limit one person’s freedom in order to preserve another’s underlines the complexity of this issue – it creates the million-dollar question. Is one person’s right to express themselves without censure as valuable as another person’s right not to be harmed by this expression? Context is vital to our answer.

The extent of the injustice suffered by either agent can be dictated by such a vast array of variables that it seems impossible to formulate any kind of pragmatic rule that would allow us to prioritise one over the other. In many cases it appears clear. Instances of hate speech or incitements to violence are easy to condemn in favour of protecting the rights of marginalised or endangered persons. At other times, the waters are murkier and there is a risk of setting a standard of censorship that endangers liberty of expression. But where do we draw the line in this instance?

Did Rushdie misuse his rights?

No. That is my categorical answer.

The content of ‘The Satanic Verses’ is definitely provocative. It is a deeply considered insult to Islam, and followers may very reasonably be offended by the text. It would be ignorant to claim that the accusations of blasphemy are surprising or unfounded. Rather, I argue that one man’s blasphemy does not impinge upon the rights of any other to the extent that his speech should be curtailed. The coexistence of belief in the modern world relies upon this principle. Blasphemy is far too subjective for its propagators to be silenced and no system of government could enforce this without total, hegemonic control.

Rushdie’s work is arguably not a genuine criticism of Islam, but an artistically constructed mockery. You would not find me writing this material, not just because I lack Rushdie’s aesthetic skill, but because I do not think that the work is particularly kind and I prefer not to cause unnecessary offence. Unkindness, however, is not a crime, and nor would I like it to be.

Salman Rushdie’s mockery of religious figures, whilst ungracious, is far from a violation of the rights of anyone in particular. In light of this novel there was no infringement upon the ability of Muslims to practise their religion, nor was there any threat to the safety of Islamic communities. Yes, Rushdie did implicitly question the validity of some Islamic beliefs, but if we cannot question or criticise a system of belief, there will never be room for debate or diversity of opinion.

It is fair for an individual to choose not to consume this material on the basis that they find it offensive. It is also fair for a person to consider the information and decide that they disagree with it, and to publicise the nature of their objection. What is unfair, is for a person to decide that their dislike is sufficient grounds to stop the spread of the material to everyone else. This doesn’t mean that book sellers, for example, must stock a novel with which they take issue, but that they would be wrong to prevent other book sellers who want to sell this novel from doing so.

A commonplace rebuke is that we have freedom of choice, but not freedom from consequences. The sentiment, although often well-intentioned, is confusing. At best, this is a profound philosophical musing about the nature of freedom. At worst, these are empty words which stymy free debate, assure group members of their infallibility, minimise the critical analysis of ideas and facilitate echo-chamber style thinking.

It’s valid to point out that we must take responsibility for our actions, and, yes, we must accept that there will be a set of consequences for whatever we choose. However, it is these particular consequences that are being debated. The argument then falls into circularity; it tells us that freedom is transactional, as we established earlier, but fails to evaluate this transaction.

Yet there are some limits to what speech is acceptable. Should it be acceptable to silence everybody with whom we disagree? No, of course not. But should people be forced to consume content that upsets them, or is in opposition to their identity, values or beliefs? Absolutely not. And further, should people who insight hatred, violence or intolerance towards others be given a platform to spread their dangerous ideologies? One is free to express something which another dislikes, but they cannot expect the other to support them, or compel violence against their opposition. We cannot tolerate intolerance.

Offense and harm

A conversation on freedom of speech thus will almost always arrive at the criminalisation of hate speech, or the right of social media platforms to remove those who they believe to be violating community guidelines. The latter is particularly relevant in the ‘cancel culture’ debate.

Simply ignoring, disagreeing or choosing not to engage with certain ideas is not adequate when the implications of these ideas are realistically threatening to the liberties of others. The notion that some social groups are owed more protection than others from freedom of speech is relevant here. This is because inciting hatred, violence or ignorance towards oppressed demographics is far more likely to have genuine consequences for its members.

The recent rise in the prevalence of misogynistic social media personality, Andrew Tate, is a prime example of this. He encourages abusive and controlling behaviour from his followers, and comments extensively that women are, and should continue to be, socially inferior to men. He has recently been banned by Facebook, YouTube and Instagram among others.

His statements cause much more than just personal offence; they perpetuate the idea that sexually abusing women is acceptable and glorify coercive and controlling behaviour. Promoting this kind of harmful conduct endangers an enormous number of people, especially when we consider that the vast majority of women will experience some kind of sexual harassment or abuse during the course of their life. This is not entertaining the thought of some far off, twisted reality but actually encouraging young men in particular to disrespect and endanger women.

A case has been made that Rushdie’s portrayal of Muhammad was part of a western narrative attempting to delegitimise Islam for centuries. Whilst Islamophobia is a real and prevalent issue, it is important to ascertain that an insult to the religion is not equitable to a promotion of harmful action against its followers.

There is a definite distinction between restricting the platforms of intolerant commentators such as Tate or removing posts which promote hatred or violence, and banning the distribution of material that challenges an ideology or belief. Individuals have the right to say, “I don’t like this belief, here is what I think”, but not to enforce the non-proliferation of disagreeable material, simply because it is disagreeable.

Freedom of expression is not without boundaries. There should, in fact, be boundaries to protect vulnerable groups and individuals. Where these limits ought to lie is still rightly the centre of an interesting and philosophically profound conversation. Yet the abhorrent act committed against Salman Rushdie will never be justified by the publication of his opinion.