Staff Writer Lara Bevan-Shiraz reflects on the life lessons she learnt whilst clowning around at École Philippe Gaulier this summer.

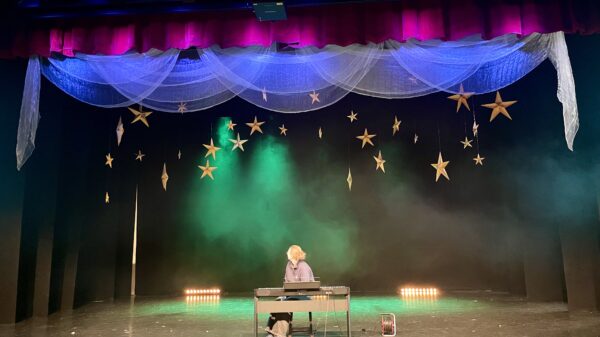

Behind the wings, no one wants to go first. Yet, the cheesy circus music has already begun. In a few short seconds, the teacher will bang his tambourine-sized drum and someone will need to step out into the blinding yellow lights. A couple more moments, some sneaky manoeuvring on the part of my peers and all eyes are fixed on me. I’m now closest to the curtain. At this point, there’s really nothing to do. Bang!

Over six weeks this summer, I threw myself headfirst into the world of clowning with no prior direct experience. Why? It sounded like a great deal of fun! École Philippe Gaulier (EPG) based in Étampes, France, presented itself as a spin-off from the Lecoq method of physical theatre, specialising in humour. The notorious reputation of the school’s eponymous founder did nothing to dissuade me. While I didn’t meet Gaulier himself, who is now over 80 and appears not to have been teaching for a couple of years, reading between the lines indicates that the new generation(s) of teachers have somewhat softened his style; even so, some peers were still driven to tears. EPG, like the Arts in general, seems to be at a turning point, replacing punishing dismissal with something closer to constructive criticism (though still incisive and curt, sometimes more than borderline – Gaulier’s wife, Michiko, sat in on a couple of lessons, adding a kind of punctuation through the loudspeakers with the sound effect of bottles being thrown at unsuccessful clowns).

My six weeks of “fun”, whilst replete with comedy, thus turned out to be rather gruelling at times. Morning movement classes added further rigour as they sought to get the students into shape. Bootcamp in style, we did hundreds of squats, planks and push-ups, our international troupe counting each set of ten in a dozen different languages and dialects. Afternoons provided limited respite, starting with the foundations of play before we progressed to a riotous explosion of clowning.

Le Jeu (The Game)

“Play” here means an unrestrained engagement with yourself, your friend(s) and your audience, without competition or self-consciousness. In Le Jeu, we use “play” as a framework to facilitate the almost untranslatable and undefinable “complicité”. As I’ve come to understand it, complicité is a kind of direct, unfiltered connection with the audience, a sense of being in it together for the fun and mischief of it, as you would be with an imaginary friend. It’s also active, constantly under maintenance. Complicité requires a continual presence and openness. At the same time, “Light on your feet” was a constant cry from our teachers in the first week – a sign of fanaticism and a loss of good faith play. The Gaulier method, typically contrarian, demanding complicité whilst screaming that demand at us!

Still, that sense of honest collaboration was integral to the activities we explored, from ball games, to tag, to dance competitions, to the downright awkward: massaging a partner’s earlobe. The latter was introduced as an attempt to provoke laughter, but those receiving this bizarre treatment were instructed to suppress any giggles. This, however, turned out not to be the true aim. The fun, both for the pairs and the audience, revealed itself when people didn’t take the rules too seriously but instead revelled in the connection and the mischief, losing happily and hopelessly. Mischief, not cut-throat rivalry. You can put your friend in a tight spot but not out of malice, rather in the spirit of play. Good complicité exists when, as in a game of tennis, the rhythm changes stroke by stroke in a rally, the audience stirred by the apparent overreach of both players striving beyond their limits.

I began applying complicité outside clown school as well: in discussions with acquaintances whose politics were polar opposite to mine and with friends with whom that connection was spontaneous. It’s not that I hadn’t done this before, but now I was consciously persisting, refusing to stop sending complicité.

As a commuter student up against the capricious Parisian RER line C, I had to rein in my inner sloth, arriving into Étampes from Paris an hour early most days to give myself three train options. Each morning, I exchanged smiles with the same weary dog walkers being dragged along at an enthusiastic pace and sat alongside fellow passengers who played a daily roulette dodging their fares. I observed the way train drivers of the same company said “hi” to one another by tooting; I watched the transition of the fields from poppies, to sunflowers, to lavender.

A minute from the school is a little public garden which catches the sun’s rays each morning. Like a terrapin, I warmed myself whilst reading a book there, greeted by the affable street sweeper as he did his daily round. I thus learnt and implemented new French colloquialisms: “Bon courage !” often replaced “Bonne journée !”; outbursts of “oh là là” and the hilarious raspberry type noise produced when one doesn’t know what to say peppered my conversations.

Complicité most naturally resides in incidental interactions like these. Where it falls apart is when we learn our incompatibilities. We see them as fated impasses not puzzles to resolve. Clowns are loved for their innocence. Their fault is to be eternal optimists: they try, and they keep trying, until they find a way to break down these walls we have built. So perhaps, we all just need to be a little more clown-like.

Keeping up this level of complicité within and outside of class is exhausting and taxing, and in a certain sense, it should be. It’s an active participation and collaboration that requires you to listen, engage and respond, all at once; still, the connections it fosters largely make up for the hardships. However, it’s incredibly draining to exhibit complicité in our fractured societies where there’s currently no reward and politics are ever more irreconcilable. You engage with eye contact, but what returns is a glazed stare. They’re playing a game at you, maybe even for an audience, but not with you. Yet those with complicité are the foundations of society, just as they are the foundations of any theatre company. We need conversations which are dialogues and not opposing monologues in order to progress cohesively. Whilst there will be outliers, if you keep sending complicité, the worst reaction you’ll get is apathy and that’s better than hostility.

“The Flop is the Friend of the Clown”

The antidote to my inner editor. Clowning required a clear, unhesitant mind: any hyper-critical commentary was secured in a soundproof box. Peace! As a writer, this nearly never happens, but as a performer, it’s essential. That’s not to say that the clown is careless and unthinking. Clowns are prepared but not rehearsed.

Clowning provides a new take on failure: “the flop is the friend of the clown” being an oft-repeated Gaulier maxim. Each time you flop and wriggle your way out of it, you make it that much easier the next time. This persistence allows you to work out what audiences do and don’t respond to and how they respond. You must be sensitive to each and every mood and focus change in your audience to realise not just when their attention drifts, but also when you have caught it. Many opportunities slip away when the clown gets afraid of losing the laugh and rapidly moves on to something else. In hoping to prolong that laugh, the clown shuts it down.

The perspective of the audience is frequently at odds with that of the clown. Often, the clown will do an action and upon completion expect the audience to be pleased. When the clown doesn’t get that reaction, they are confused, at which point the audience laughs at the clown’s irrepressible earnestness. Life is the same: we are our own worst critics. Where we see failure, someone else will see a seed ready to take root.

Interpretation is dependent upon the viewpoint of the interpreter. In one exercise, five of us were spaced out in a row, all strictly facing the audience, with glances amongst our ensemble forbidden. The person at the right-hand end of the row was instructed to come up with and perform an action (make a cup of tea, wash the dishes, etc). Then the person directly adjacent would try to copy what they had seen from their peripheral vision and so on and so forth until the person on the other side of the room did their impression of the action. The first and last actions ended up completely unrelated. Each individual put their own interpretation and imprint on the actions, often inadvertently, be that a balletic flair or a hesitation in their movement. Even in conversations, we don’t realise what we give away. We “um”, repeat our favourite words and use unique intonations. We also listen differently, retaining certain information according to our respective inclinations and predispositions. We just realise more when clowns do it. They, like all comics, push the limits, making us uncomfortable even in our laughter when we recognise ourselves in a parody.

The little notebook I took with me to France is crammed full of quotes and discoveries. It even has a hasty sketch of a car crash, doodled to express the pent up sentiments of a particularly hard day. Reflecting upon these experiences, I am acutely aware that the thoughts that captured my attention then no longer do. We give weight to our preoccupations according to the intensity of the moment when we should really consider the brevity of the present. The clown does not worry whether the audience will laugh tomorrow, but whether they are laughing now.

In the end, what has emerged from those six weeks at clown school is not a sure career in clowning, but a sharpening of perspective. Things won’t go as planned, but that’s okay. I’ve got some tricks up my sleeve to save a flop and maybe even steal a laugh.