Roar writer Charmaine Tan on the struggles of wanting to break into the film industry as a female.

“Are you sure that you want a career in film? It’s filled with toxic masculinity,” the sound recordist asked as we wrapped up the film set. Having been on many shoots with a predominantly male crew and a lack of female directors, this statement shouldn’t have been surprising. Yet, coming from a male professional himself… It felt like a reality check.

A quick look at the figures reveals Hollywood’s persistent “woman problem.†Men outnumber women 4 to 1 in key roles, only 4 out of 276 films from 2016 to 2018 had female key grips, and only 5 women have ever been nominated “Best Director†for an Oscar throughout a century. Until today, Kathryn Bigelow remains the only female to ever win a “Best Director” Oscar.

Are female directors just terrible at what they do?

Given how skewed the aforementioned figures are, as well as the fact that 50% of film school graduates are actually women but only 4% of cinematographers and 12% of directors are, it’s tough to look at these alarmingly low statistics without asking if there’s at least some unconscious bias at play.

Many enter the film industry initially through working on film sets as below-the-line crew; others start by making indie films and looking for sponsors. In the first instance, the problem lies in the fact that there are very few female crews, which could very well be explained by the biological factor of men being more muscular than women. As a result, men are more adapted to carrying heavy equipment, a task that often comes hand-in-hand with many below-the-line roles. Hence, it would make sense to have a more male-dominated workforce. However, how do we explain these discrepancies resulting from the latter group of aspiring filmmakers – the indie filmmakers who seek sponsors?

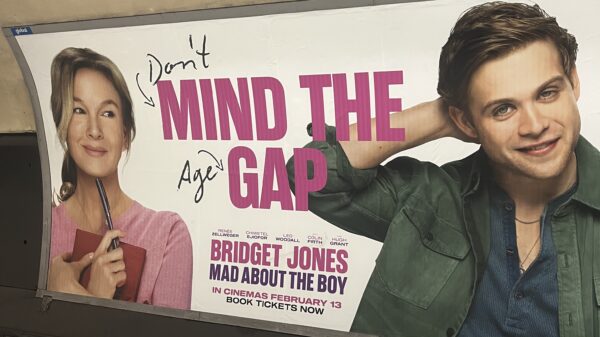

There is an unconscious bias that directors tend to be male – type “film director†in Google if you don’t believe me. The results that appear are mostly male. This is a problem because sponsors tend to see women as incompetent or non-director material, therefore increasing their chances of rejection more than their male counterparts. According to film reporter Alicia Malone, “men are hired and promoted on potential,†whilst “women are hired and promoted on proof.†It is precisely due to this image of the male director that women are often viewed as a risk and don’t get past the stage of pitching and getting sponsored. While some may argue that women are simply bad at negotiation, it is for that same reason that indie films tend to be more gender-inclusive than big-budget Hollywood blockbusters.

Moreover, we should consider the fact that many women actually pioneered filmmaking. It’s hard to buy the theory that they are simply terrible at it when one of the first fiction films ever made (“La Fée aux Choux“) was created by a woman by the name of Alice Guy-Blaché. It doesn’t end there: Lois Weber experimented with split-screen and cross-cutting decades before they formally became cinematic techniques. Hollywood wasn’t always a man’s world, and women actually dominated silent films back in the early 1900s.

It was only during the inter-war years and after the Great Depression that Hollywood became a lucrative business. Movie-making became something more than a passion; it was a way to make money. Gender roles were also becoming increasingly defined during this period. Women were thought to be homemakers and mothers, whilst men, breadwinners. Consequently, the female workforce in film fell globally, which is illustrated by Hollywood’s “Golden Age” where there had only been one female filmmaker (Dorothy Arzner).

Why does this matter?

First and foremost, it affects the kind of stories we see on screen. Be it the perspective of a story told (male/female gaze), the theme (coming-of-age films by female directors tend to be more well-received), or the characters, a film is capable of connecting or dividing us. Think back to all the times you watched a documentary and felt the immense urge to act, or all the times you walked out of a movie theatre, feeling cathartic, drained, inspired. Films incite feelings in us. They tell stories which are personal, relatable, shared. “Booksmart,” “Miss Representation,” “Reversing Roe” – these are stories about women, from the perspective of women. They spark conversations about societal issues that need to be talked about, which concern mainly women. Hence, having female filmmakers directly affects the kind of entertainment we see and the conversations that go on around us.

Secondly, it has been proven that a female director (or any head position, for that matter) is a direct causation of a more gender-balanced crew. This is especially important because a more gender-balanced film set means less sexual harassments, something especially widespread within the film industry despite the statement being true for any workplace. Therefore, the 1:22 female/male director and 6:94 female/male cinematographer statistics need to change.

What can we do?

Support female filmmakers. If you like the stories they tell, go to the movies and watch them. Bring all your friends. Support female-oriented collectives that empower female filmmakers. If you’re a director, check out sites like illuminatrix and hire a female cinematographer. If you’re the executive of a big company, be open to pitches by female directors; be more willing to take that “risk.” Remember, more female directors mean more diverse crews.

Lastly, spread the idea that women can be filmmakers. We can be directors, producers, key grips, writers, editors, anything, everything. Share images of female filmmakers. Share the knowledge that filmmaking was actually pioneered by many women. It’s Women’s History Month now, so what better time to talk about this? We need to work together to eliminate the stigma against female filmmakers.

But above all, maintain realistic expectations. Celebrate that women occupied 20% of key roles in the industry in 2019, achieving a “historic high,†but without forgetting that a 20-80 ratio is still extremely unbalanced. Definitely rejoice at the fact that there have been more “high-profile breakthroughs†in the recent years, including Patty Jenkins (“Wonder Woman”) and Greta Gerwig (“Lady Bird”), but without losing track of how women directors are still severely under-represented.

Understand that change takes time and effort. And if you’re contemplating a career in film, like me, the question isn’t whether you want to be a female director. It’s whether you want to be a director.